I ask you, what am I? I’m one of the undeserving poor: thats what I am. Think of what that means to a man. It means that hes up agen middle class morality all the time. If theres anything going, and I put in for a bit of it, it’s always the same story: “Youre undeserving; so you cant have it.” But my needs is as great as the most deserving widow’s that ever got money out of six different charities in one week for the death of the same husband. I dont need less than a deserving man: I need more. I dont eat less hearty than him; and I drink a lot more. I want a bit of amusement, cause I’m a thinking man. I want cheerfulness and a song and a band when I feel low. Well, they charge me just the same for everything as they charge the deserving. What is middle class morality? Just an excuse for never giving me anything.

—G. B. Shaw, “Pygmalion” (1914)

Author: Eric MacKnight

Why is learning to write well so slow, so difficult, and so frustrating?

Why is writing so difficult?

For many reasons. For example, writing is not natural, like talking or walking, so it requires a special effort. It also requires careful attention to lots of annoying details like punctuation, grammar, and spelling. Many of the ‘rules’ for English punctuation, grammar, and spelling don’t make much sense. Moreover, writing requires you to do two conflicting things at the same time: think about what you are saying, and also think about how you are saying it. And so on. To put it briefly, writing well is one of the most difficult human skills.

Why is it so frustrating?

Because usually, improvement takes a long time. Even worse, improvement is not gradual. That is, if we made a graph of writing improvement it would NOT look like this:

Instead, a graph of writing improvement would look something like this:

The second graph helps to explain an almost universal experience: you work, and work, and work, but your results don’t improve. Why? Because you are on one of those long, flat portions of the line. If you let the frustration defeat you, then you give up trying and you never reach the next level. But if you remain patient and determined and keep working, you will eventually reach that point where everything you have been working on suddenly ‘clicks’ and you jump up to the next level.

So now you want to know . . .

How does one become a good writer?

It’s not so complicated, but it’s not so easy, either.

- Read! When you read, you learn what words and sentences look like when they are written. If you read very little, your understanding of what written words and sentences look like remains weak and uncertain. How is that word spelled? Should I put a comma here? What’s the right way to use a dash, or a semi-colon? Hundreds of such questions confront a writer, and it’s impossible to learn the answers to them by memorizing a grammar book. However, someone who reads a great deal learns to answer most of those questions correctly simply by seeing so many words spelled and so many sentences and paragraphs written correctly. So there’s the first key to success as a writer: good writers are voracious readers!

- Pay attention. Once you become an enthusiastic reader—when reading is a pleasure, not a chore—you can begin noticing how writers write. After all, if you enjoy reading, then you enjoy the results of someone else’s writing. At first, and for a long time perhaps, you may be content just to benefit from other people’s hard work. But if you’re lucky you will develop an interest in the craft of writing—how do they do that?—and want to try it yourself. You may discover that, although writing well is very difficult, the satisfaction of succeeding at it is very great.

- Write! You learn to walk by walking, and not giving up even though at first you fall down a lot. You learn to play the piano by playing the piano. You learn carpentry by doing carpentry. You learn to play football by playing football. You learn to write by writing. Find good writers, and copy what they do. Then find others who write very differently, and copy what they do. Practice, practice, practice. Seek out good coaches, and take their advice.

And as Winston Churchill almost said, never, never, never, never give up.

The oranges of Republican support for Trump’s serial lies

The embrace of Donald Trump’s shameless serial lying by the Republican Party did not fall suddenly out of the sky. It began in the first term of George W. Bush’s presidency, and first surfaced in an article published in the New York Times Magazine. Wikipedia:

The phrase was attributed by journalist Ron Suskind to an unnamed official in the George W. Bush administration who used it to denigrate a critic of the administration’s policies as someone who based their judgements on facts. In a 2004 article appearing in the New York Times Magazine, Suskind wrote:

The aide said that guys like me were ‘in what we call the reality-based community,’ which he defined as people who ‘believe that solutions emerge from your judicious study of discernible reality.’ […] ‘That’s not the way the world really works anymore,’ he continued. ‘We’re an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality. And while you’re studying that reality—judiciously, as you will—we’ll act again, creating other new realities, which you can study too, and that’s how things will sort out. We’re history’s actors…and you, all of you, will be left to just study what we do’.

International relations scholar Fred Halliday writes that the phrase reality-based community (in contrast to faith-based community) was used “for those who did not share [the Bush administration’s] international goals and aspirations”. . . .

The term was used to mock the Bush administration’s funding of faith-based social programmes, as well as a perceived hostility to professional and scientific expertise among American conservatives.

This attack on reality by the political Right developed further as “post-truth politics,” a

term . . . used by Paul Krugman in The New York Times to describe Mitt Romney’s 2012 presidential campaign in which certain claims—such as that Barack Obama had cut defense spending and that he had embarked on an “apology tour”—continued to be repeated long after they had been debunked. Other forms of scientific denialism in modern US politics include the anti-vaxxer movement, and the belief that existing genetically modified foods are harmful despite a strong scientific consensus that no currently marketed GMO foods have any negative health effects. The health freedom movement in the US resulted in the passage of the bipartisan Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994, which allows the sale of dietary supplements without any evidence that they are safe or effective . . . .

So after Trump is gone and Republicans want to blame him for everything, don’t let them off the hook. And don’t let the Democratic establishment off the hook, either, for their support of elitist policies that enriched Wall Street, drained the middle class dry, and turned vast swaths of rural America into a desperate, meth-lab-strewn wasteland.

More than the worst thing we’ve ever done

Each of us is more than the worst thing we’ve ever done.

Visualization for healing

During this COVID-19 pandemic it may be useful to try visualization to speed healing, not as a substitute for medical care but to supplement it. At any rate, the calming effects of such exercises can’t do any harm. There are a lot of somewhat goofy sites on the internet on this topic, and many trying to sell a product of some kind, but the Meditation Society of America has a pretty good take on it. Here are the first four of eight approaches to visualization for healing that they suggest:

1. In your minds eye, see aberrant or inflamed cells changing into healthy cells. If there is a damaged or corrupted area within the cells, visualize them changing and becoming free from injury. See your whole body becoming pure. Visualize yourself as perfectly healthy.

2. There are cells within your body that act as protectors and actually attack and kill damaging invader cells. See these warrior cells destroy those cells that could cause you injury. See your whole body becoming pure. Visualize yourself as perfectly healthy.

3. There are cells within your body that eat threatening cells. See them devour the harm causing structures. See your whole body becoming pure. Visualize yourself as perfectly healthy.

4. Visualize groups of healthy cells combining to replace any damaged areas of your body. For instance, if you have suffered a broken bone, see the cells come together in healing, bonding together to reform a complete structure. Visualize the bone as perfectly healthy.

The article quotes Dr. Herbert Benson, founder of the Mind/Body Medical Institute of Harvard Medical School in 1988 and of the Mind/Body Medical Institute at Massachusetts General Hospital in 2006:

We know that belief can lead to healing or at least improvement in 50 percent to 90 percent of diseases, including asthma, angina pectoris, and skin rashes, many forms of pain, rheumatoid arthritis, congestive heart failure. They’re all influenced by belief. We in medicine have made fun of belief by calling it the “placebo effect,” or insisting that “It’s all in your head.” Yet, belief is one of the most powerful healing tools we have in our therapeutic arsenal.

It might be worth a try. Click on this link for the full article from the Meditation Society of America.

Fado!

Fado is Portuguese folk music that is found almost exclusively in Lisbon.

I went there for a teachers’ conference in 1989 when I was working in Morocco. The guy that was supposed to pick us up at the airport was late, so I and a couple of buddies bought a map and jumped on a city bus. We talked up a friendly girl, who told us the name of a restaurant in the Bairro Alto (an old neighbourhood of the city) where we could hear good fado. That’s the first time I heard the word.

The restaurant was a family-owned greasy-fish place filled with locals drinking cheap red wine and eating greasy fish. We sat down and ordered food (and cheap red wine) with the help of Cristina, daughter of the owner, who spoke enough French for us to communicate. There was a guitar leaning against the wall, but nothing else. After a while a nondescript fellow wandered in, shook a few hands, then picked up the guitar and started singing this amazing music, with the locals singing along on the choruses. After about 15 minutes he put the guitar down, joined a table, and had his meal.

As the evening progressed this happened repeatedly, with different singers coming in, doing a set, and then either sitting down for a glass of wine or wandering off, presumably, to the next place. How or if they got paid was unclear.

Finally, about midnight, there was this scruffy looking guy with the guitar. Our waitress, Cristina, took off her apron, walked up to join him, and began singing like Maria Callas. She and the guy began doing a kind of duet, but clearly it was improvised, with lots of snarky back-and-forth between them and the crowd roaring with laughter.

We stayed as long as we could, and went back repeatedly during our three-day conference. Cristina, it turns out, had recorded an album, and she sold me a tape cassette of it. The tape was good, but in person she was magnificent.

Of course we didn’t understand a single word of the lyrics, but it didn’t matter. The music was so beautiful, and powerful, and sad. One guy told me, “Fado is the Portuguese blues.”

Here is the great Amália Rodrigues:

And here, more recently, is Carlos Manuel Moutinho Paiva dos Santos Duarte, whose stage name is Camané:

Enjoy!

The un-patriotic rich

You’ve heard about the “Greatest Generation” and how Americans all pulled together in the 1940s to win the war against fascism, right? Doris Kearns Goodwin, in her book No Ordinary Time (1994) tells a different story.

As Hitler occupied most of France and began attacking England, FDR appealed to business leaders to shift their production to defense materials. They refused unless they would be given preferential status in bidding for defense contracts. In the end, FDR gave in.

When the revenue bill [giving favorable terms to corporations taking on defense contracts] finally passed later that fall, the capital strike [by big business] came to an end and war contracts began to clear with speed.. . . In the months ahead . . . new legislation would be enacted to try to increase the relative share of small business in total army procurement. But by then, the basic pattern—the link between big business and the military establishment, a link that would last long into the postwar era and lead a future president to warn against the “military-industrial complex”—was already set.[pp. 158-59]

In 1940, . . . approximately 175,000 companies provided 70 percent of the manufacturing output of the U.S., while one hundred companies produced the remaining 30 percent. By the beginning of 1943, the ratio had been reversed. The hundred large companies formerly holding only 30 percent now held 70 percent of all government contracts.[p. 399]

To this day, Franklin Roosevelt remains the symbol of big government and the controlled economy. Yet, under Roosevelt’s wartime leadership, the government entered into a close partnership with private enterprise . . . . Business was exempted from antitrust laws, allowed to write off the full cost of investments, given the financial and material resources to fulfill contracts, and guaranteed a substantial profit. The leader who had once proclaimed his intention to master the forces of organized money had become their greatest benefactor.[pp. 607-08]

So angry was the outpouring of public sentiment that a resolution was introduced in the Senate requiring members to renounce their claim of special privilege. When the defiant Senators defeated the resolution by a vote of sixty-six to two, the public mood darkened.[p. 357]

The Black Death in Italy, 1348

Giovanni Boccaccio (1313-1375) begins his masterwork, The Decameron, with a vivid first-hand description of the bubonic plague’s arrival in Florence, Italy, in 1348. By the time it was all over, historians estimate that roughly one third of the population of Europe was dead. Boccaccio describes the disease itself—

. . . it began with swellings in the groin and armpit, in both men and women, some of which were as big as apples and some of which were shaped like eggs, some were small and others were large; the common people called these swellings gavoccioli. From these two parts of the body, the fatal gavaccioli would begin to spread and within a short while would appear over the entire body in various spots; the disease at this point began to take on the qualities of a deadly sickness, and the body would be covered with dark and livid spots, which would appear in great numbers on the arms, the thighs, and other parts of the body; some were large and widely spaced while some were small and bunched together. And just like the gavaciolli earlier, these were certain indications of coming death. . . .

. . . the rags of a poor man who had just died from the disease were thrown into the public street and were noticed by two pigs, who, following their custom, pressed their snouts into the rags, and afterwards picked them up with their teeth, and shook them against their cheeks: and within a short time, they both began to convulse, and they both, the two of them, fell dead on the ground next to the evil rags.

—and the human responses to incomprehensible suffering:

Because of all these things, and many others that were similar or even worse, diverse fears and imaginings were born in those left alive, and all of them took recourse to the most cruel precaution: to avoid and run away from the sick and their things; by doing this, each person believed they could preserve their health. Others were of the opinion that they should live moderately and guard against all excess; by this means they would avoid infection. Having withdrawn, living separate from everybody else, they settled down and locked themselves in, where no sick person or any other living person could come, they ate small amounts of food and drank the most delicate wines and avoided all luxury, refraining from speech with outsiders, refusing news of the dead or the sick or anything else, and diverting themselves with music or whatever else was pleasant. Others, who disagreed with this, affirmed that drinking beer, enjoying oneself, and going around singing and ruckus-raising and satisfying all one’s appetites whenever possible and laughing at the whole bloody thing was the best medicine; and these people put into practice what they heartily advised to others: day and night, going from tavern to tavern, drinking without moderation or measure, and many times going from house to house drinking up a storm and only listening to and talking about pleasing things. These parties were easy to find because everyone behaved as if they were going to die soon, so they cared nothing about themselves nor their belongings; as a result, most houses became common property, and any stranger passing by could enter and use the house as if he were its master. But for all their bestial living, these people always ran away from the sick. With so much affliction and misery, all reverence for the laws, both of God and of man, fell apart and dissolved, because the ministers and executors of the laws were either dead or ill like everyone else, or were left with so few officials that they were unable to do their duties; as a result, everyone was free to do whatever they pleased. Many other people steered a middle course between these two extremes, neither restricting their diet like the first group, nor indulging so liberally in drinking and other forms of dissolution like the second group, but simply not going beyond their needs or satisfying their appetite beyond the necessary, and, instead of locking themselves away, these people walked about freely, holding in their hands a posy of flowers, or fragrant herbs, or diverse exotic spices, which sometimes they pressed to their nostrils, believing it would comfort the brain with smells of that sort because the stink of corpses, sick bodies, and medicines polluted the air all about the city.

—Translated from the Italian by Richard Hooker (1993)

The entire text, in an older translation, can be found online here: https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/source/boccacio2.asp. If your eyes are like mine, you will want to enlarge your screen’s display resolution to read it.

Talkin’ Bout My Generation, and Yours

A granfalloon is a proud and meaningless association of human beings.

—Kurt Vonnegut, Wampeters, Foma & Granfalloons (1974)

As COVID-19 wends its way through North America, I have been noticing recurrent news items regarding the behaviour of young people in the early stages of this massive public health crisis: continuing to go out to bars, movies, and restaurants; thronging beaches in Florida; and so on. Most young people, it appears, don’t vote, even when inspired by old socialists like Bernie Sanders. They like the rallies, but they don’t vote. And they don’t follow the news, which seems to account for some of their recent clueless activities.

Most of them haven’t stopped eating meat or driving cars, either, or done much of anything else to reduce their “carbon footprint,” as far as I can tell.

All of which reminds me of that internet meme, “Okay, Boomer,” mocking my generation, telling us to get out of the way since we’ve made such a mess of things. Let the younger generations take over and try to repair the damage before it’s too late.

But it’s not about generations. It has never been about generations. When my friends and I were protesting the Vietnam War and marching for civil rights and advocating for gender equality, we were always a minority among our generational peers. When we were educating ourselves about the imperialist crimes committed by the U.S. government, and becoming conscious of the racist and sexist ideas we had grown up with, and learning to prepare vegetarian meals and grow our own food, we were always a minority. Most of our fellow “Boomers” were always unenlightened, materialistic, and conventional.

In every generation, the enlightened minority sees most clearly, pays attention, raises the alarm, protests against injustice, agitates for necessary change. The majority, as Thoreau wrote in his great essay, “On Civil Disobedience,” lags always at least a step behind.

To those “woke” young people tempted to mock the Boomers: have a look first at the majority of your peers, who are just as unenlightened and clueless in the face of climate change or COVID-19 as most of my peers were in the face of Vietnam, segregation, and CIA coups all across Latin America and beyond.

Boomers are not the problem. The problem is the clueless majority—of all ages.

Three greats in one great photo

Louis Armstrong, Billie Holiday, and Barney Bigard.

From Wikipedia: New Orleans is a 1947 American musical romance film featuring Billie Holiday as a singing maid and Louis Armstrong as a bandleader; supporting players Holiday and Armstrong perform together and portray a couple becoming romantically involved. During one song, Armstrong’s character introduces the members of his band, a virtual Who’s Who of classic jazz greats, including trombonist Kid Ory, drummer Zutty Singleton, clarinetist Barney Bigard, guitar player Bud Scott, bassist George “Red” Callender, pianist Charlie Beal, and pianist Meade Lux Lewis. Also performing in the film is cornetist Mutt Carey and bandleader Woody Herman.

On the Wet’suwet’en pipeline protests: An open letter to BC Premier John Horgan

Dear Premier Horgan,

Difficult as it might be, I hope you will call for a pause on construction of the natural gas pipeline through Wet’suwet’en land—a pause during which all parties will seek a consensus.

The government has won in the courts, but there is no consensus among the Wet’suwet’en, and opposition to the pipeline remains fierce.

In the tradition of Western democracy, a majority vote and a court decision are enough to go forward. In First Nations cultures, however, the community needs consensus before going forward.

Reaching consensus will be a long, difficult process. It may not even be possible, in the end. But in such a worse-case scenario, would abandoning the pipeline project really be more costly than the damage that will be done to relations among Canadians by going forward without consensus?

With my best wishes,

On the 2020 U.S. Presidential Election

So, summing up, we have a situation with multiple baked-in weaknesses:

- Major media, easily manipulated

- Social media, a cesspool of propaganda and disinformation

- A public divided into tribes

- An anti-democratic Electoral College

- An anti-democratic U.S. Senate

- An election process that costs each candidate millions and millions of dollars, i.e., an open invitation to corruption

And who, looking at all that, could possibly foresee a good result?

Rules for following the U.S. presidential election on social media:

- Any message on social media that makes you think, “That’s it, I will NEVER vote for THAT Democrat!” is, until proven otherwise, part of a disinformation campaign, and should be ignored.

- And people described as “progressive activists” who do & say disgusting things should be regarded as provocateurs working for Republicans, until proven otherwise.

If you are wondering whether the best strategy to defeat Trump is “move to the centre” or “go left!” this podcast conversation with data-nerd political scientist Rachel Bitecofer will interest you:

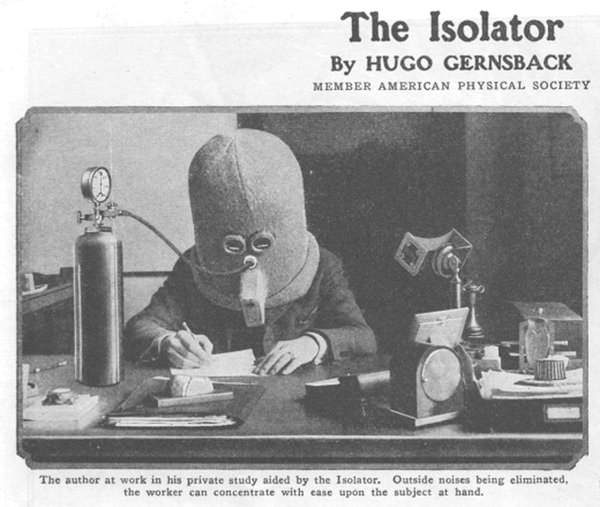

The Isolator

A century ago, shutting out distractions was already a problem. Today, perhaps, the Isolator’s time has finally come.

H/t: “The History Lovers’ Club” Twitter feed.

Ignorance and cruelty

I’ve never understood why the seven deadly sins don’t include ignorance and cruelty. They have anger and gluttony and lust in there, but I’d much rather have a person eat three slices of apple pie but be kind and well informed. Gluttony doesn’t come anywhere close to ignorance. I’m not talking about stupidity. I’m talking about failing to be informed and to deliberately cut yourself off from knowing things. That must lead to every kind of error there is.

—Louis Naidorf, architect

Naidorf designed the iconic circular Capitol Records building in Los Angeles. He is quoted in this profile in Billboard magazine.

Sugar addiction: no longer a metaphor

Most people hear the phrase “sugar addiction” as a metaphor. A new study from Denmark indicates that sugar addiction is literal. Dr. Michael Winterdahl, one of the scientists who led the study, wanted to refute the idea that sugar was physically addictive. The evidence changed his mind:

“After just 12 days of sugar intake, we could see major changes in the brain’s dopamine and opioid systems. In fact, the opioid system, which is that part of the brain’s chemistry that is associated with well-being and pleasure, was already activated after the very first intake,” says Winterdahl.

The study from Aarhus University is explained in layman’s terms in this article from MedicalXpress.com. The technical English-language summary on the Aarhus University site is here.

For more about sugar, see my post on the Good Habits blog, “Kick the sugar habit—or it will surely kick you.”

On the murder of Qasem Soleimani

Why are crimes not called crimes if they are committed by the US government?

Can we stop calling the murder of Qasem Soleimani a “mistake” or a “blunder”? It was a crime. Murder.

Those who refuse to call it murder are complicit in excusing it.

Soleimani, we are told, deserved to die because he was a bad man who committed terrible crimes. Fine. The proper response to crime is arrest, indictment, and trial—not summary execution.

Imagine if nations behaved like citizens governed by the rule of law, instead of organized crime families trying to maximize their power and putting out hits on their rivals.

American History

Slaveowners declaiming eloquently about freedom, and

merchants declaiming eloquently about the evils of taxation,

create a new nation

populated largely by brash, ignorant, racist know-nothings

who spin a wonderful myth about Success and the American Dream

and convince themselves that they are both the Good Guys

and (eventually) the Greatest Nation on Earth,

smugly confident that power and virtue can be perfectly aligned

in America.

Ignoring the crimes committed in their name,

they are astonished when their victims strike back.

“They hate us because we are free!” they cry,

as if that makes any sense at all.

And even now, after Civil Rights and Vietnam,

after Iraq and Afghanistan,

after Roe v. Wade and marriage equality,

after legalized marijuana and Black Lives Matter,

when everyone who’s woke gets their news

from TV comedians,

when a self-proclaimed socialist finishes second

in the Democratic presidential primaries—

even after all that, Hillary Clinton (!) gets three million more votes

but still loses the election

because of the anti-democratic Constitution

written by those slave-owning Founders,

and the anti-democratic Republicans in the Senate refuse

to acknowledge the obvious crimes committed by their president

whose re-election will depend on a few thousand votes in a handful

of white-majority midwestern states cast by

people who know nothing about

American history.

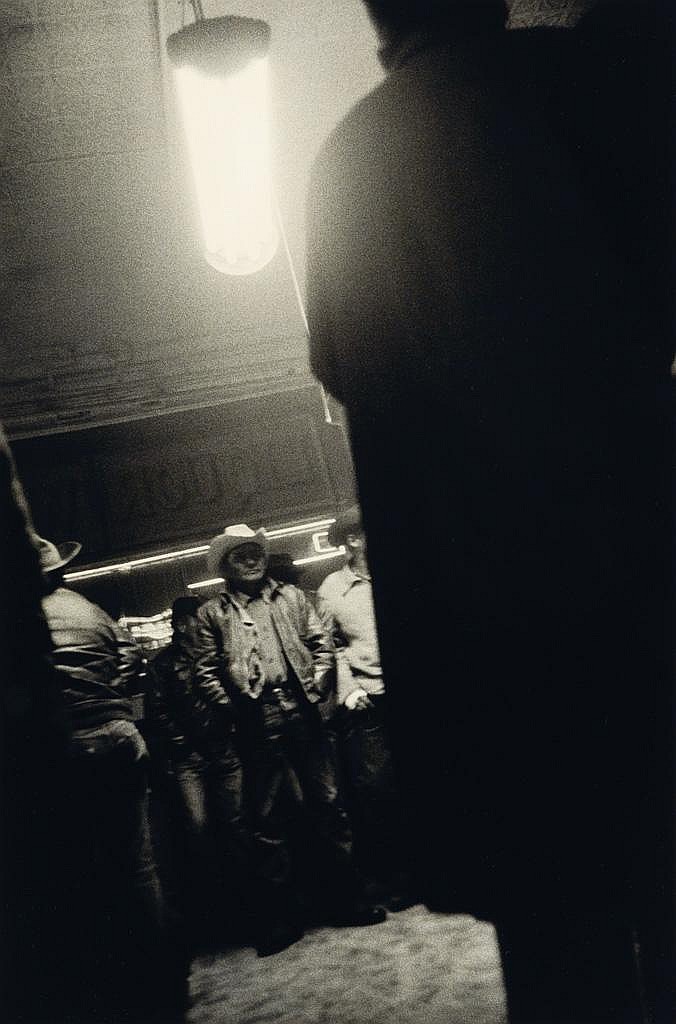

Robert Frank, “The Americans”

With brilliant insight and economy, Frank revealed a country that many knew existed but few had acknowledged. He showed a culture deeply riddled by racism, alienation, and isolation, one with little civility and much violence. He depicted a society numbed by a seemingly endless array of consumer goods that promised many choices but offered no real satisfaction, and he revealed a people emasculated by politicians who were fatuous and distant at best, messianic at worst.

Socialize pro sports!

Reading about the insane and obscene contracts being handed out to Major League Baseball’s most elite free-agents has reminded me of one of my better brilliant-ideas-that-will-never-happen.

Let’s socialize pro sports.

Crazy, eh? Read on.

Each team would be owned by its city. Players would be paid well, but not exorbitantly, according to a league-wide pay scale and salary cap. Players would have generous post-career packages that made sure they had plenty of opportunities to obtain further education and build a second career. And the biggest stars could still cash in on the side with endorsement deals, etc.

Players would cease to be nomads with a list of teams on their resumés. Trades would still happen, but not—as is so often the case today—as salary dumps. For the most part, team rosters would be stable.

Fans would be supporting their team, and cheering for their players, instead of supporting some billionaire’s team and cheering for the latest gang of rent-a-players to put on the team uniform.

Ticket prices could return to affordable levels for middle-class fans.

The bulk of the TV revenues and other profits would go to the owners—that is, the cities—and be used for roads, schools, hospitals, recreation facilities, etc.

“Objection!” you say. “My city government has messed up everything else already—I don’t want them firing coaches and GMs, too. And what about the possibilities for corruption?”

And I say: you’ve got to be kidding.

How could the hiring and firing of team management get any worse than it is now? And how could a bit more government graft be worse than a small pack of billionaires and millionaires taking everything? Maybe city ownership of teams would inspire a bit more participation in the democratic process; how bad could that be?

And I haven’t even mentioned the current scandalous conditions under which cities are extorted into subsidizing stadiums for billionaire owners who threaten to pack up and move elsewhere if they don’t get the sweet deal they demand.

To hell with all these billionaires. Socialize pro sports so we can root for teams that are really ours.

Christmas Poem 2019

The Impeded Stream

by Wendell Berry

It may be that when we no longer know what to do,

we have come to our real work.

And that when we no longer know

which way to go,

we have begun our real journey.

The mind that is not baffled

is not employed.

The impeded stream

is the one that sings.

The center of serenity

The love of Heaven and Earth is impartial,

and they demand nothing from the myriad things.

The love of the sages is impartial,

and they demand nothing from the people.

The cooperation between Heaven and Earth

is much like how a bellows works!

Within the emptiness there is limitless potential;

in moving, it keeps producing without end.

Complaining too much only leads to misfortune.

It is better to stay in the center of serenity.

—Laozi, Dao De Jing, Chapter 5, translated by Yuhui Liang

TOK Assessment (IB Diploma Programme)

I just resumed teaching TOK after a hiatus of four years, but I began teaching the course in 1987 and have taught it almost every year since then.

My two cents’ worth:

The major problem with TOK assessment is that there are only two marks—the essay and the presentation—whereas in other courses there are several. Result: one anomalous mark can really skew the final grade.

Solution: Add a short-answer TOK question to each of the exams in other subject areas.

Besides increasing the number of marks that go into the final grade for TOK, this would have the added benefit of involving all subject teachers in TOK (whereas in the overwhelming number of cases presently, DP teachers who do not teach TOK know nothing about it). This would help restore TOK to its intended role at the center of the DP curriculum.

I do not imagine that this suggestion will make it into the 2020 course update. It would take time, of course, to develop short-answer TOK questions for each subject area. But I hope that it will be seriously considered for future improvements to the programme.

Too much stupid

How many stupid things can a nation do, and how stupid can its leaders and its people be, before the nation falls into an irreversible spiral of decline?

The underlying factor behind the stupidity is addiction. Modern society is an addiction culture. Everything that drives economic activity involves some kind of addiction, and addiction makes people stupid. Try using charts, data, and facts to explain to a junkie why he should stop using heroin. Now do the same and try to convince people to give up junk food and junk entertainment and junk consumerism.

Neil Postman was right in 1985 in his book, Amusing Ourselves to Death: in the television age, everything is entertainment. In the internet age, all the factors Postman identified have increased geometrically. So we are told that in the UK people are “tired” of hearing about Brexit, and that in the US people are “fed up” with talk about impeachment. Low entertainment value. Change the channel.

Timothy Leary’s 1960s call to the hippie generation to “turn on, tune in, drop out” has been co-opted by the commercial addiction juggernaut—as has been everything else that dissidents of any sort have put forward. The society as a whole has turned on to addictions of all sorts, tuned in to culture as entertainment, and dropped out of any serious engagement with political life.

Decline and fall, baby.

For a more technical and data-based version of this analysis, read “This is How a Society Dies,” by Umair Haque.

Quality vs. Taste: The Ice Cream Story

No ice cream was consumed during the writing of this story, and consuming ice cream of any kind is NOT recommended. If you want something sweet, eat fruit.

One Saturday afternoon my friend and I were walking down the pedestrian-only section of the main shopping district downtown. My friend looked to the left and saw a Mr. Softie vendor selling swirls of soft ice cream in three different colors, with sprinkles of various kinds available at additional cost. “Oooh! Mr. Softie!” he cried, and started toward the stand. “Wait!” I said. “Do you have any idea what’s in that stuff? It’s just air and chemicals and artificial sweeteners and artificial flavors and artificial colors. The only real thing about it is the very real damage you do to yourself when you put that poison in your body.” “I know,” he said. “It’s crap, and it’s really bad for me, but I love it anyway.” And off he went.

Waiting for him amid crowds of shoppers, I began looking around. On the opposite side of the street to the Mr. Softie stand was a Waldorf-Ritz Gourmet Ice Cream shop. The best, most expensive, and most delicious ice cream in the world! Without hesitating I walked through the ornate double doors, already salivating as I imagined a scrumptious bowl of Waldorf-Ritz Rocky Road. The moment I passed through the doors, lights began flashing, celebratory music began playing, and confetti began falling from the ceiling. The store manager rushed straight up to me, smiled happily, and said, “Congratulations, sir! You are the one millionth customer to walk through those doors!” He took me by the arm and led me to a special roped-off table that had been prepared for the occasion. “Please have a seat here, sir,” he said. Then he called to his employees, “Bring out the Prize Ice Cream!” In a kind of procession, the entire staff escorted the master ice cream chef to me as he carried, on a silver tray, a large bowl of ice cream. “There you are, sir!” said the manager. “Three scoops of our unbelievably delicious pistachio ice cream, free of charge, with our compliments. I know you will enjoy it.”

I looked at the ice cream, and then at the circle of happy employees waiting to see me take my first spoonful, and then at the manager. “I really appreciate this,” I said, “but I’m sorry to say that I don’t like pistachio ice cream.” The manager looked shocked, but then smiled. “I think you misunderstand, sir,” he said. “This ice cream is handmade in small batches by our master ice cream chef. All the ingredients are 100% natural, organic, and completely free of any artificial additives or colorings of any kind whatsoever. The cream comes from cows raised in luxury dairy farms where they are treated like movie stars. Nowhere in the entire world will you find ice cream even half as good as Waldorf-Ritz Gourmet Ice Cream!”

“I know that your ice cream is the best in the world,” I sighed. “But I don’t like pistachio ice cream!”

The moral of this sad tale, of course, is that judgments of quality are different from judgments of taste. I may love Mr. Softie ice cream, or I may love a corny movie or a trashy piece of pop music, even though I know that if I judge their quality, they all fail the test. On the other hand, I may admit that Waldorf-Ritz Pistachio ice cream or the novels of James Joyce or the ballets of Igor Stravinsky are all superb examples of ice cream, fiction, and dance, while still not enjoying any of them. In the words of the great American film critic, Roger Ebert, “Does it make a movie ‘good’ because you ‘like’ it? No, it doesn’t, and I have liked a lot of bad movies.” We can put this another way: no one can tell you that your judgments of taste are wrong. No one can say, “You are wrong to dislike pistachio ice cream!” But if someone who knows more than you do about literature and ballet says, “You are wrong to claim that the novels of James Joyce or the ballets of Igor Stravinsky are crap,” he just may be correct.

Malcolm X on education

Education is an important element in the struggle for human rights. It is the means to help our children and our people rediscover their identity and thereby increase their self respect. Education is our passport to the future, for tomorrow belongs only to the people who prepare for it today.

—Malcolm X, Speech at Founding Rally of the Organization of Afro-American Unity (28 June 1964), as quoted in By Any Means Necessary (1970)

John Adams on education

Education makes a greater difference between man and man, than nature has made between man and brute.

—Letter to Abigail Adams (29 October 1775)

John Adams: “Remember, democracy never lasts long”

Remember, democracy never lasts long. It soon wastes, exhausts, and murders itself. There never was a democracy yet that did not commit suicide. It is in vain to say that democracy is less vain, less proud, less selfish, less ambitious, or less avaricious than aristocracy or monarchy. It is not true, in fact, and nowhere appears in history. Those passions are the same in all men, under all forms of simple government, and when unchecked, produce the same effects of fraud, violence, and cruelty.

—John Adams, Letters to John Taylor (1814)

Orwell pulls no punches

From “Looking Back on the Spanish Civil War” (1942):

The broad truth about the war is simple enough. The Spanish bourgeoisie saw their chance of crushing the labour movement, and took it, aided by the Nazis and by the forces of reaction all over the world. . . .

The Fascists won because . . . they had modern arms and the others hadn’t.

. . . the British ruling class did all they could to hand Spain over to Franco and the Nazis. Why? Because they were pro-Fascist, was the obvious answer. . . . Whether the British ruling class are wicked or merely stupid is one of the most difficult questions of our time . . . .

. . . the people who support or have supported Fascism . . . are all people with something to lose, or people who long for a hierarchical society and dread the prospect of a world of free and equal human beings. . . . the simple intention of those with money or privileges to cling to them. . . .

All that the working man demands is what these others would consider the indispensable minimum without which human life cannot be lived at all. Enough to eat, freedom from the haunting terror of unemployment, the knowledge that your children will get a fair chance, a bath once a day, clean linen reasonably often, a roof that doesn’t leak, and short enough working hours to leave you with a little energy when the day is done.

Another great Kenny Clarke photo

The ballad seems to be having its effect on the couple in the background.

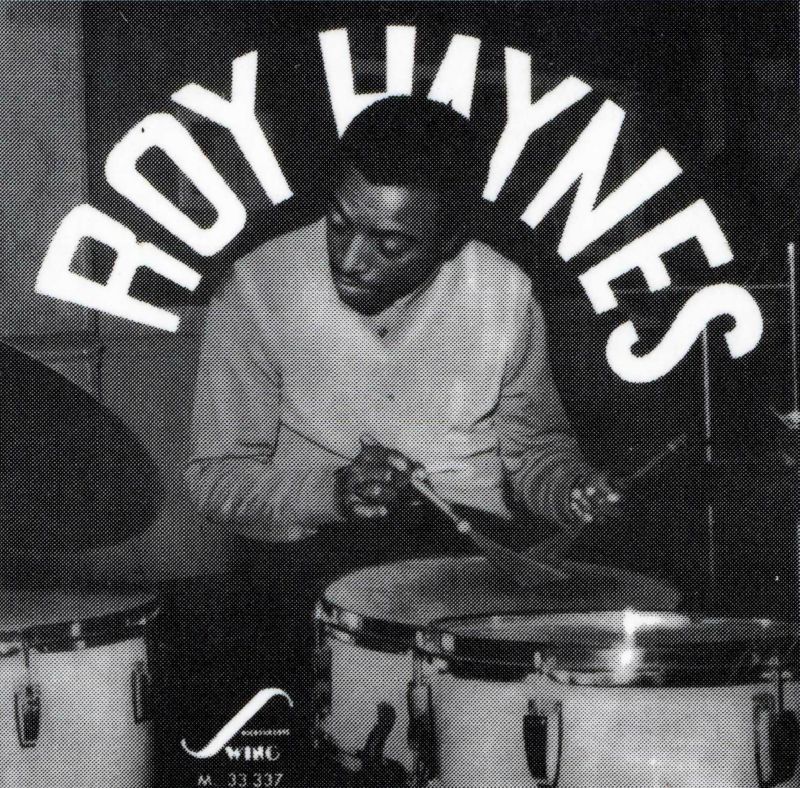

Roy Haynes ca. 1954

One of the truly great drummers. Always musical, always tasteful.

My Old Friend

for all of my old friends

My old friend lives far away

from me and

I live far away

from my old friend.

We send email back and forth

from time to time,

a photo, a song, or

something in the news.

I am a part of my

old friend’s life,

only a part,

and my old friend is a

part of my life, too,

but just

a part.

We share good memories.

One day my email will not be answered.

Or perhaps

one day I will not

be here to open

my old friend’s message.

One of us will become

pure memory.

Sooner or later

both of us will

disappear into the

land of eternal forgetting.

The teacher’s vocation

In La gloire de mon père, Marcel Pagnol remembers one of his father’s colleagues, who graduated from teacher’s college first in his class. From there he went straight into a job in the worst neighbourhood in Marseille, a part of town where no one dared to walk at night. He stayed there, teaching in the same classroom for forty years.

Marcel overhears his father ask this man one evening,

“So, you never had any ambition?”

“Oh yes,” he said, “I did! And I think I have succeeded very well. Just think: in twenty years, my predecessor saw six of his former students guillotined. As for me, in forty years I have only seen two, plus one who was reprieved. That’s made it all worthwhile.”

A reasonable creature

I believe I have omitted mentioning that in my first Voyage from Boston, being becalm’d off Block Island, our People set about catching Cod and haul’d up a great many. Hitherto I had stuck to my Resolution of not eating animal Food and on this Occasion, I consider’d with my Master Tryon, the taking every Fish as a kind of unprovok’d Murder, since none of them had or ever could do us any Injury that might justify the Slaughter.

All this seem’d very reasonable.

But I had formerly been a great Lover of Fish, and when this came hot out of the Frying Pan, it smelt admirably well.

I balanc’d some time between Principle and Inclination: till I recollected, that when the Fish were opened, I saw smaller Fish taken out of their Stomachs: Then, thought I, if you eat one another, I don’t see why we mayn’t eat you. So I din’d upon Cod very heartily and continu’d to eat with other People, returning only now and then occasionally to a vegetable Diet.

So convenient a thing it is to be a reasonable creature, since it enables one to find or make a reason for everything one has a mind to do.

—Benjamin Franklin, Autobiography

Moderates vs. radicals: we have been here before

From the “History Doesn’t Repeat, but Sometimes It Rhymes” Dept:

In the early days of France’s Third Republic (ca. 1870 – 1890), the major political divide was between monarchists, who wanted a king again, and republicans, who favoured parliamentary democracy.

The moderate republicans, called “opportunists” because they thought new laws should be introduced only when they were expedient, wanted to avoid disruptive issues, to limit the scope of reform, and to deal with one problem at a time. “Nothing must be put in the republican program that the majority of the nation cannot be induced to accept immediately,” Gambetta had said, as spokesman of the opportunist point of view. The radicals, on the other hand, wanted to carry through sweeping reforms at once. . . .

Meanwhile, the mass of the French people remained indifferent to the republic or were becoming increasingly radicalized as a result of the government’s resistance to programs designed to improve the lot of industrial and agricultural workers. . . .

Meanwhile, in the Austro-Hungarian empire,

In 1890 militant German and Slavic nationalists combined to prevent . . . compromise on the nationalities question. In 1891 both Czech and German moderates were routed in the parliamentary elections. . . .

[Prime Minister Taafe failed] to solve the serious financial problems of the empire. . . . Instead of meeting the problem with a large-scale program of tax and financial reform, Taafe simply increased the rate of state borrowing, thereby raising the cost of servicing the national debt.

. . . [His] efforts at social reform were also ineffective. . . . Taafe’s proposals for universal suffrage and labor reform offended every vested interest in the country. . . .

The political response . . . was the spectacular growth of the Christian Socialist movement [led by Vienna mayor] Karl Lueger (1844 – 1910) [who] championed the rights of the worker, peasant, and small businessman against big business and “Jewish” capitalism. He advocated a socialist welfare state . . . where Slavs, Jews, and Protestants would not be welcome. Lueger was enormously popular and was repeatedly elected mayor of Vienna.

—Norman Rich, The Age of Nationalism and Reform, 1850 – 1890 (1977)

The obvious parallels with current events in Europe and the U.S. should concern all of us. The Industrial Revolution, the growth of the middle class, and the rise of Western democracies are not finished stories. Neither is the U.S. struggle over slavery and its transformation after 1865 into a struggle over racial equality. These stories continue; the history continues. Our era did not begin in 1945, or in 1900, but in Paris in 1789, and we still do not know how the political, economic, and racial issues unleashed in the French Revolution will finally sort themselves. A racist, authoritarian triumph is not out of the question.

Lack of consensus + poor leadership = big, big trouble

The failure of genuine parliamentary government . . . was due . . . to the absence of the feature most necessary for its successful operation: broad agreement among the main power groups in a country about fundamental issues.

. . . The crucial power to determine government policy remained in the hands of the executive leadership. Hence the quality of leadership in every country was at all times of paramount importance.

—Norman Rich, The Age of Nationalism and Reform, 1850-1890 (1977)

“A martial government, under whatever charming phrases, will engulf the democratic world”

In England and the United States, in Denmark, Norway, and Sweden, in Switzerland and Canada, democracy is today sounder than ever before. It has defended itself with courage and energy against the assaults of foreign dictatorship, and has not yielded to dictatorship at home. But if war continues to absorb and dominate it, or if the itch to rule the world requires a large military establishment and appropriation, the freedoms of democracy may one by one succumb to the discipline of arms and strife. If race or class war divides us into hostile camps, changing political argument into blind hate, one side or the other may overturn the hustings with the rule of the sword. If our economy of freedom fails to distribute wealth as ably as it has created it, the road to dictatorship will be open to any man who can persuasively promise security to all; and a martial government, under whatever charming phrases, will engulf the democratic world.

—Will Durant, The Lessons of History (1968)

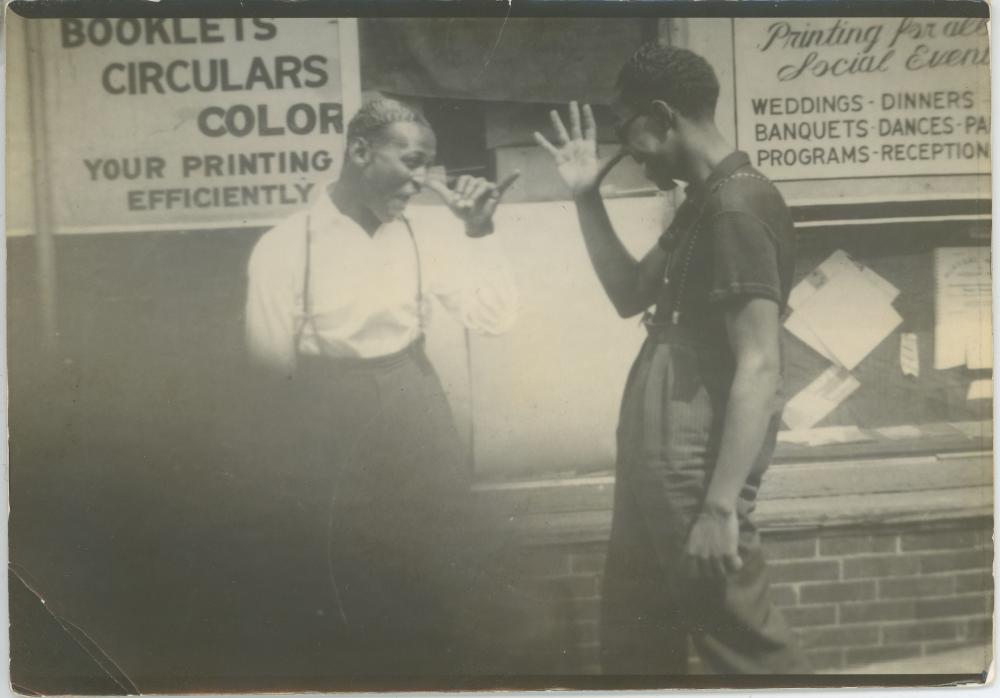

Kansas City, 1938

Jesse Price (L) and Charlie Parker (R) horsing around in the summer of 1938. Price was 19, Parker a year younger. Jesse Price was a drummer and singer who worked largely as a sideman but made a few great recordings as a band leader and vocalist in the early days of R&B, similar in style to early Louis Jordan. “Frettin’ for Some Pettin'” (1948) and “Jump It With a Shuffle” are great examples of his work. Photo credit: American Jazz Museum.

Wise words from a Russian anarchist

“We are convinced that liberty without socialism is privilege, injustice; and that socialism without liberty is slavery and brutality.”

—Mikhail Bakunin, 1867

Voltaire: I am silent, I have too much to say

My dear brother, my heart is withered, I am crushed. . . . I am tempted to go and die in some foreign land where men are less unjust. I am silent, I have too much to say.

—From a letter written 7 July 1766, on hearing of the torture and execution of the chevalier de La Barre. La Barre’s body was burned along with a copy of Voltaire’s Dictionnaire philosophique.

Voltaire on wasting one’s breath

I had more sense than to argue with him, since there is no possibility of convincing an enthusiast. A man should never inform a lover of his mistress’s faults; nor tell someone involved in a lawsuit that his case is weak; nor attempt to persuade a fanatic by strength of reasoning.

—Voltaire, Lettres philosophiques