‘There now, Mister, that’ll do. It’s the Chief’s orders that you’re to come along quiet. We’re going to take you to Bywater and hand you over to the Chief’s Men; and when he deals with your case you can have your say. But if you don’t want to stay in the Lockholes any longer than you need, I should cut the say short, if I was you.’

To the discomfiture of the Shirriffs Frodo and his companions all roared with laughter. ‘Don’t be absurd!’ said Frodo. ‘I am going where I please, and in my own time. I happen to be going to Bag End on business, but if you insist on going too, well that is your affair.’ . . .

‘Look here, Cock-robin!’ said Sam. ‘You’re Hobbiton-bred and ought to have more sense, coming a-waylaying Mr. Frodo and all. And what’s all this about the inn being closed?’

‘They’re all closed,’ said Robin. ‘The Chief doesn’t hold with beer. Leastways that is how it started. But now I reckon it’s his Men that has it all. And he doesn’t hold with folk moving about; so if they will or they must, then they has to go to the Shirriff-house and explain their business.’

‘You ought to be ashamed of yourself having anything to do with such nonsense,’ said Sam. . . .

‘ . . . What can I do? . . .

‘ . . . You can give it up, stop Shirriffing, if it has stopped being a respectable job,’ said Sam.

‘We’re not allowed to,’ said Robin.

‘If I hear not allowed much oftener,’ said Sam, ‘I’m going to get angry.’

‘Can’t say as I’d be sorry to see it,’ said Robin, lowering his voice. ‘If we all got angry together something might be done. But it’s these Men, Sam, the Chief’s Men. He sends them round everywhere, and if any of us small folk stand up for our rights, they drag him off to the Lockholes. . . . Lately it’s been getting worse. Often they beat ’em now.’

—J. R. R. Tolkien, The Return of the King

Category: Politics & History

Another Golden Age of excellence financed by exploitation?

The “Golden Age” of ancient Athens in the 5th century B.C.E. included fabulous sculptures and architecture, the glorious dramas of Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides, and philosophers like Socrates and Plato. Ironically, these glories were financed by slave labour in Athens’ silver mines, and by the revenues of the Athenian Empire. The empire had begun as a defensive league, led by Athens, to protect against attacks from Persia. Over time, however, Athens wielded despotic power over its “allies.” One wonders how many thoughtful Athenians reflected that their achievements were founded on exploitation.

I thought of this the other day while reading about the complaints of some Los Angeles Dodgers fans about the team’s ownership. In recent years the team’s athletic and organizational excellence has been unsurpassed. They just won their third World Championship in the last six seasons, and their second in a row, in a gruelling, often amazing seven-game series against the Toronto Blue Jays. On the other hand, the team’s hedge-fund billionaire owners are said to be invested in ICE detention centres while raking in millions from their many Latino fans and featuring several Latino players on their roster. Social media posts are decrying this hypocrisy, calling for disinvestment in detention centres and private prisons, and calling on the team to refuse the traditional White House invitation granted to the World Champions.

The parallels with ancient Athens are easy to trace. Will this new “golden age,” with its astonishing achievements alongside a widening wealth gap and increasingly onerous exploitation by a small coterie of billionaires, lead to the same sort of dismal collapse suffered by Athens in the 4th century B.C.E.? Stay tuned.

Addendum: From 2019, another of my universally-ignored brilliant ideas: Socialize pro sports!

1950 – 2000: a golden age?

A friend wrote:

Looking back on the range of our lives, I think we’ve lived in a golden time, notwithstanding some awful things—the Vietnam War being the most predominant—but we have lived in a time when our country was king of the world and stood for morality. Obviously, we did awful things secretly—see Brazil, Guatemala, etc.—but overall, at least we stood for helping others, beginning with the Berlin airlift, and now all of that has been destroyed.

Well, yes, but . . .

For privileged, educated middle- and upper-middle-class Americans, the post-WWII era was a kind of liberal paradise in many ways. Well-funded public schools, often staffed with the last generation of women teachers whose like in the future would opt for medical school, or law school, or careers as corporate executives. Safe, clean neighbourhoods in often new suburban developments. Girl Scouts, Boy Scouts, Little League, Friday night football games at the local high school. Generous financial aid for college education. Free speech, faith in progress and an even better world in the future. Rising standards of living; each generation a bit better off than their parents. The ugly past of slavery and two World Wars and the Holocaust and the Great Depression all consigned to history. Optimism!

But for racialized and marginalized minorities, the picture was quite different. We don’t really need to go into the poverty, the redlining, the police abuse, the excessive rates of incarceration, the exclusion from schools, jobs, housing, and in the South, transportation, lodging, even parks and recreation. We all know now, I hope, about the FBI’s COINTELPRO campaign to slander, arrest, and murder Black activists and anyone else threatening the status quo. But let’s go back to those idyllic white suburbs. I remember being on the playground or sitting on the curb in my neighbourhood trading baseball cards. When we felt we had been cheated, we said we had been “jewed” or “gypped.” I had no idea what these words meant, but they show how pervasive such attitudes were. Non-whites and non-Christians were “other.” They were feared and disliked. They were mistreated if they came near enough to be mistreated. They were segregated, either formally or informally, into Black areas, Jewish neighbourhoods, Latino neighbourhoods, Indian reservations, and we white people never strayed into such areas. I remember being on the bus with the high school football team and the pep band in 1966 or 1967, going to an “away” game versus a school with a large Hispanic population. We chanted, in chorus: “Tacos, tacos, greasy, greasy, we can get this one, easy, easy!” The racism was casual, automatic, baked in, unquestioned, and ubiquitous.

Meanwhile, for the white American working class, their post-war paradise was all about good union jobs in factories—jobs that paid much better than the jobs those suburban college kids could aspire to. Rising incomes, good pensions and benefits, own your own home, two cars in the driveway, a vacation cottage, maybe a boat, holidays in Vegas or Honolulu. All-white neighbourhoods and schools, mostly all-white workplaces, with the better jobs held almost exclusively by whites. Church every Sunday. Saturday night in the tavern or at the bowling alley. For the young, rock ‘n roll, fast cars, hot dates. The tough guys would go into Hispanic or Black neighbourhoods and pick fights. Remember West Side Story? In the early ’70s I was hitchhiking in Idaho and got a ride with some young cowboy types, not much older than I was. They told me that one of their favourite entertainments was beating up drunken Indians.

There was a good deal of violence at home, too. Corporal punishment for the kids at school and at home, not just spanking with the hand but with paddles or belts. Domestic violence by a generation of men dealing with undiagnosed post-war trauma who self-medicated with alcohol and then took out their frustrations on their wives, girlfriends, and children. Even the jokes were typically cruel and demeaning. Taunts and physical bullying were thought to be an essential part of a child’s upbringing, especially for the boys, who had to be tough to survive in a tough world. No one wanted to be a sissy or a cry-baby. The playgrounds were often dangerous, frightening places where you either had to stand up for yourself or find a protector who would stand up for you.

In elementary school we ordered cheap paperbacks from the newsprint Scholastic catalogs that were given out to us three or four times a year. I remember the heroic portrayals of FBI agents protecting us against communists, defending our freedom. On television I watched westerns in which the bad guys really did wear black hats and the good guys wore white hats, and I learned that America was the good guy riding the white horse and doing the right thing all over the world, spreading freedom to the dark places where bad people were in charge. The racist subtext escaped me. It was JFK’s murder that started to wake me up to the lies. Edmund Wilson’s introduction to Patriotic Gore presented the Cold War not as a struggle between Good (us) and Evil (them), but as “the irrational instinct of an active power organism in the presence of another such organism, of a sea slug of vigorous voracity in the presence of another such sea slug.” I learned that good, kindly Dwight Eisenhower, the hero of World War II, had approved the assassination of Patrice Lumumba in the Congo because he threatened US access to vital mineral resources; and that Ike had cancelled a promised referendum in Vietnam after being informed that Ho Chi Minh’s communists would almost certainly win any such vote. And so on. The white hat remained, but instead of representing Good it seemed instead to represent racial and national dominance, both political and economic. This correction of the picture painted by US propaganda in the 1950s need not go to extremes: no one I know, given a choice, would have preferred to live in the Soviet Union or in China or in Castro’s Cuba (unless, like Assata Shakur, you were on the FBI’s Most Wanted list).

So, yes, the half-century that followed the Second World War was a kind of liberal golden age, so long as you were a white American or Western European (and, preferably, male). And perhaps the ideals that either fueled or masked (or both) the dark side of that golden age—perhaps those ideals are in the end more important than the lies and shortcomings behind or beneath them. I had a conversation years ago about the hypocrisy of Thomas Jefferson, a slaveowner who kept an enslaved mistress and fathered several children with her and then denied their paternity. How could such a man assert that “All men are created equal” in a document called the “Declaration of Independence”? And the cabbie I was talking with—a brown-skinned immigrant—unfazed by Jefferson’s scandalous behaviour, just smiled and said, “Well, maybe his beautiful words are more important than how he lived.”

From the “Words Matter” Department: The Assassination of Henri IV

The great event during the Descartes brothers’ years at La Flèche was the interment of Henri IV’s heart in the school chapel in 1610. Henri IV had been assassinated by a Catholic religious fanatic named Ravillac, who was incensed at Henri IV’s plan to invade Germany to help Protestants against the Catholics of the Holy Roman Empire. Ravillac leaped into the king’s carriage and stuck a knife into the very heart that was now being ceremoniously delivered to the college church.

So the Jesuits and the Catholic League (who never forgot that Henri IV was formerly the Protestant king of Navarre) finally got Henri IV, who wanted to go to war with holy Spain. The view that the Jesuits and the Catholic League instigated the assassination, however, is not a very popular way of stating the matter among Catholic historians. What happened is that a student from the Jesuit college at Clermont in Paris had tried to assassinate Henri IV in 1596 and failed. Then Ravillac, another Catholic student, got him.

It is classic. The Jesuits had been teaching the perfidy of Henri IV for years. This or that priest had told his students that France would be better off if Henri IV was dead: Will no one rid us of this man? As has happened more than once in such circumstances, some dedicated young man decided to do the deed in the name of God. He acted alone. The Jesuits were not to blame.

—from Cogito Ergo Sum: The Life of René Descartes (2002), by Richard Watson

Coda

Despite the Jesuits’ hatred of Henri, his heart was interred, according to his wishes, at the collège he had founded, and was joined later by the heart of his queen, Marie de Medici. In 1793, during the Revolution, when Jesuits, Bourbon monarchs, and foreigner queens were equally despised, both hearts were burned in the public square.

So it goes.

World War II, up close and personal

Rick Atkinson’s excellent World War II trilogy—The Army at Dawn, The Day of Battle, and The Guns at Last Light—provides a comprehensive history of the war’s three great invasions in the Western theatre: North Africa, Italy, and the final campaign from Normandy to Germany. It punctures some of the hagiographic portraits of American leaders that I grew up with, and it honestly includes the sordid side of war, from bedbugs in Yalta to the epidemic of venereal disease that followed the liberation of Paris. Atrocities were committed on all sides, from the murder of captured soldiers to the looting of captured towns and widespread rapes committed by victorious soldiers—not to mention the bombing of civilians in cities on both sides of the conflict, and of course the monstrous Nazi extermination camps.

Atkinson does not sanitize the story. The “Allies” struggled with each other for precedence and prestige, often descending to the level of whiny children. Operations were a series of endless screw-ups, with colossal waste of men and equipment. No one ever seemed to learn that bombing civilians leads not to surrender, but to stiffened resistance. The single omission I noticed was Atkinson’s failure to mention the havoc wreaked among surviving soldiers and their families by PTSD.

In the end, Hitler and fascism were defeated, and Atkinson closes his trilogy with a poetic paean to what he clearly thinks was, despite all of its ugliness, a noble cause. This may or may not strike readers as overly sanguine. Today the 1945 defeat of fascism seems more like an armistice, at best. Certainly there is no ceasefire in Ukraine, or in Gaza, and ICE agents in the U.S. are doing a pretty good imitation of Nazi thugs. The dream of a world without war, discrimination, bigotry, racism, and exploitation seems remote indeed.

This!

Vicious Romans

Thomas Wiedemann’s thin volume, Cicero and the End of the Roman Republic, begins with this sentence: “The values of the Roman republic into which Cicero was born were both militaristic and competitive”—a claim amply supported by the next 83 pages of murders, treachery, slander, and endless legal battles consisting largely of ad hominem attacks. I confess to skimming more and more quickly. The Chinese phrase puts it succinctly: 他们都是流氓, “they are all gangsters.”

That *other* 9/11 . . . more like Jan 6

From the “Plus ça change . . . ” Dept: France experienced an epidemic of political violence in 1937, culminating in September and November.

The most spectacular bombing happened on 11 September, when two devices exploded in the Etoile district of Paris, causing significant material damage and killing two police constables. The culprits were two French men, René Locuty and Lêon Macon. Both men were members of the secret extreme right-wing group, . . . the “Cagoule.” Eugène Deloncle, a veteran of the 1930s extreme right, directed the Cagoule, while wealth French business interests bankrolled the organization. . . . The French police had long kept the Cagoule under surveillance, yet the authorities were motivated to act only when Deloncle launched an abortive coup on 15 November 1937. In January 1938, Minister of the Interior Marx Dormoy exposed to the French public the frightening scale of this terrorist organization’s plot against the Republic. Nonetheless, so thoroughly associated with “unFrenchness” was terrorism at this time that the existence of a French terrorist group was difficult to believe, a fact that Deloncle’s allies in the right-wing press and political establishment played upon.

—Chris Millington, The Invention of Terrorism in France, 1904-1939

Let’s see . . . terrorism associated with foreigners . . . right-wing groups secretly financed by rich right-wing businessmen . . . our own people wouldn’t do such things . . . . Sounds strangely familiar, eh? Same old song, different names.

And then Millington adds this: “If right and left perceived different enemies behind terrorism in France, each side considered the matter with reference to broader long-established anxieties over the “immigrant problem” and the porosity of French borders.”

Tell me about it!

Unending Conflicts: Reflections on “The Longest Day” and “The Last Battle,” by Cornelius Ryan

Listening to the audiobook version of Cornelius Ryan’s account of the fall of Berlin, The Last Battle, read by the fabulous Simon Vance, inspired me to buy the audiobook of The Longest Day—which turned out to be much better than the Hollywood movie, despite the monotonous sing-song intonations of the reader, Clive Chafer.

In The Longest Day Ryan highlights the tremendous good luck that blessed the Allies, and the amazing foul-ups that doomed the Germans. First, the stormy weather that told the Germans the invasion could not possibly occur in early June, and the break in the weather that was just long enough to push Eisenhower to give the go-ahead. Then, the first group of Army Rangers attacking the cliffs at Pointe-du-Hoc missed their landing spot, causing a delay in their reaching the top of the cliffs; as a result, their reinforcements, hearing nothing from them by the agreed hour, diverted to Omaha Beach, which probably saved the Americans from being driven back into the sea there. On the German side, Hitler was convinced that the Normandy landings were a feint, and that the real invasion would arrive in the Pas-de-Calais. Rommel left Normandy to go home to Germany for his wife’s birthday on the 6th, and to see Hitler to persuade him to release to him the reserve Panzer tank division. In his absence, the Germans badly miscommunicated the early reports of the landings, and Hitler delayed release of the Panzers until it was too late to drive the Allies off the beaches. By the time Rommel was finally alerted and got back to Normandy, the Allies had a firm foothold in Europe and Germany’s defeat, caught between Eisenhower in the west and the Russians in the east, was inevitable. In short: the success of the D-Day landings was almost a miracle.

The Last Battle, like The Longest Day, weaves its narrative around portraits of a diverse collection of Germans, Russians, Americans, Brits, and others of all sorts, both civilian and military. The accounts of atrocities committed by the advancing Russians, often in revenge for atrocities committed by German soldiers in Russia, are recounted in some detail. Among the German leaders, the cowardly Himmler and the vainglorious Göring vie in ignominy with the sycophantic yes-men surrounding Hitler, who by this time was a shrivelled, delusional basket case. But even the best of the Germans, like Heinrici, despite their intelligence and courage, were using their undeniable talents to support a regime of psychopathic bigotry and brutality.

As a child I would come home from school and watch WWII movies on television. They seemed like ancient history to me. Later I realized that the end of the war had been just 15 years before my afternoon television entertainments. Later still I realized that many of the fathers of my schoolmates had fought in the war. Today as I read news reports of the war in Ukraine, the atrocities in Gaza, and the neo-fascist ICE raids in the U.S., I realize that the Second World War did not end, really, but merely paused to catch its breath, like the American Civil War. These conflicts flare up into overt violence, then subside to uneasy truces, then flare up again, but seem never to end.

Some big, fantastic notion

E. F. Schumacher’s Small is Beautiful (1973) remains a fount of wisdom—wisdom which is in short supply today, and which we need. Desperately.

The way in which we experience and interpret the world obviously depends very much indeed on the kind of ideas that fill our minds. If they are mainly small, weak, superficial, and incoherent, life will appear insipid, uninteresting, petty and chaotic. It is difficult to bear the resultant feeling of emptiness, and the vacuum of our minds may only too easily be filled by some big, fantastic notion—political or otherwise—which suddenly seems to illumine everything and to give meaning and purpose to our existence. It needs no emphasis that herein lies one of the great dangers of our time. —E. F. Schumacher

The economy is more important

The economy is more important, so we must continue using fossil fuels.

The economy is more important, so we must stop wearing masks and tracking deaths from the pandemic.

The economy is more important, so we must continue degrading the environment.

The economy is more important, so we cannot stop doing business with murderous dictators.

The economy is more important, so we cannot prioritize human rights.

The economy is more important, so we cannot spend more on schools, hospitals, and low-income housing.

And so on.

Environmentalists need to get behind nuclear power

Why? Because the only options to nuclear are 1) fossil fuels, or 2) no-growth, and neither of those is a viable option.

Nuclear power sucks, but only in the same way that everything else in an industrialized society does: multinational corporations, international banks, big tech. None of this is going away; the only hope is to manage it through sensible and effective regulation.

Wind and solar are great, but limited. Only nuclear power can supply enough energy to replace what we get now from oil, coal, and gas—as well as powering the inevitable growth in developing economies. France has been using nuclear power successfully for decades. It is long past time for the environmental movement to stop the fear-mongering about nuclear power and begin the hard work of expanding its use as quickly and safely as possible.

Not all regions need nuclear power, or are well suited to it. Coastal British Columbia, for example, prone to earthquakes and with plenty of capacity for wind- water-, and even solar-generated electricity, is not ideal for nuclear power. Eastern BC and Alberta, on the other hand, make a lot of sense for nuclear development, particularly in Alberta, where nuclear power could displace the oil and gas industry and re-train and re-employ its workforce.

UPDATE, 23 September 2025: Andrew Nikiforuk, writing in The Tyee, begs to differ in “The New Nuclear Fever, Debunked” https://thetyee.ca/Analysis/2025/09/22/New-Nuclear-Fever-Debunked/. My responses: 1. I wish he had mentioned France, where nuclear power seems to have been a successful component of the French energy system for many years. 2. If the main problem with nuclear power is cost overruns caused by corruption, then maybe we should . . . address the corruption? And 3. In conclusion, Nikiforuk writes,

An honest and imperfect response to the climate crisis would require a political, behavioural, economic and moral transition that would systematically reduce our energy and material consumption at an unprecedented pace. But that’s not an action any modern politician seems to be able to contemplate, let alone discuss.

So, if that’s the case (and it seems correct to me) then . . . what? The demand for energy will not level off or decrease until we reach a general global collapse. Continuing to burn fossil fuels leads straight to that outcome. Solar, wind, and hydroelectric power can never fully replace the energy currently produced by fossil fuels. So unless we are prepared just to resign ourselves to catastrophe, nuclear power has to be part of the way forward, along with other green energy and conservation measures, and whatever the difficulties involved—red tape, corruption, waste disposal, etc.—we had better start facing up to them.

Ron Chernow’s “The House of Morgan” (1990)

Chernow tells the story of the Morgan banking dynasty from the 1850s to the 1980s—as sobering and depressing a tale as one could ever care to read. From the earliest days onward, the Morgan crowd was invariably on the wrong side: against workers and unions, in favour of monopolists, always on the side of the super-rich. In the 1920s and 1930s, the Morgans (J. P. Morgan, Morgan Grenfell, Morgan Guaranty, Morgan Stanley, etc.) financed the rise of fascist governments in Japan, Italy, and Germany. Any Latin American despot who offered stability and profits became a client, with Juan Peron of Argentina at the top of the list. Beginning in the 1970s they tapped into Arab oil money—an effort aided by their longstanding anti-Jewish policies. They bitterly resisted any and all efforts at banking regulation, which they branded as “socialist” and “communist.” And they found ways to make money out of every war from the Civil War on. They rode the wave until finally being reduced to just another Wall St. company at the end of the dog-eat-dog cowboy financing of the 1980s.

The story is depressing, first, because the Morgans made billions from being on the wrong side; and second, because of how empty and soul-destroying their lives were. Mansions, estates, yachts, limousines, hobnobbing with royalty, gold-plated fixtures, and all their time spent thinking about how to make more money. It is hard to imagine a more boring group of people.

U.N. identifies companies complicit in Israel’s Gaza genocide

The U.S. response: sanction the author of the report: https://apnews.com/article/francesca-albanese-gaza-genocide-sanctions-un-israel-ff0501f318b7dd0d923c30f10b639724.

| Lockheed Martin Leonardo S.p.A (Italian arms manufacturer) FANUC (Japanese) Microsoft Alphabet (Google) Amazon IBM Palantir Technologies Caterpillar Rada Electronic Industries Hyundai Volvo Booking |

Airbnb Drummond Glencore Chevron BP Bright Dairy & Food (Chinese) Orbia / Netafim (Mexican) BNP Paribas (French) Barclays BlackRock Vanguard Allianz AXA |

Mark Carney: A Canadian Macron?

Just as the French elected Emmanuel Macron to stave off a surge of support for Marine Le Pen’s far right populism, so Canadians have elected the Liberal Party led by Mark Carney to stave off the threat of Pierre Poilievre’s poisonous right-wing populism. Both men are former bankers. Macron, for all his strutting and showboating internationally, has been a disappointment domestically, failing to satisfy either conservatives or progressives. In Canada, progressives who normally would have voted for Green Party or NDP candidates voted Liberal, hoping that Carney would not only save us from Poilievre and stand up to Trump, but would also effectively address the climate crisis and the housing shortage.

So far, he has talked tough about U.S. aggression, but accomplished little. He has snuggled up to the Albertan oil and gas lobby, apparently in what is surely a doomed attempt to win over enough Albertans to break the Conservatives’ stranglehold on the province and tamp down the nutbar secession movement; but has done nothing to promote carbon-free energy development. And he has pushed through a bill that will accelerate construction projects, alarming both environmentalists and indigenous groups.

It is very early days, and I hope to be proved wrong, but at the moment Carney seems headed toward the same fate as Macron.

Meanwhile in the U.K., the Labour Party under Keir Starmer is criminalizing peaceful protest and free speech by anyone who happens to object to genocide in Palestine, while the neo-fascist revolution in the U.S. is proceeding briskly. We are living, as the fake “Chinese curse” says, in interesting times.

[To be updated as events unfold.]

Aïda Amer’s American Flag

Perfectly expresses the moment we are witnessing.

Source: https://www.aidaamer.com/?itemId=c7s6obglfrjh2iruhz1l854iwlixvw

French military discipline, 1914

As the French army falls back toward Paris in the face of an overwhelming German advance, the Minister of War, Adolphe Messimy, decides that the ineffective General Victor-Constant Michel must be replaced as Military Governor of Paris. At the same time, a majority of the newly-formed coalition government decide that Messimy must himself be replaced. Barbara Tuchman, in The Guns of August, picks up the story:

Michel stormed when asked by Messimy to resign, protested loudly and angrily and obstinately refused to go. Becoming equally excited, Messimy shouted at Michel that if he persisted in his refusal he would leave the room, not for his own office at the Invalides, but for the military prison of Cherche-Midi under guard. As their cries resounded from the room Viviani fortuitously arrived, calmed the disputants, and eventually persuaded Michel to give way.

Hardly was the official decree appointing Gallieni “Military Governor and Commandant of the Armies of Paris” signed next day when it became Messimy’s turn to storm when asked for his resignation by Poincaré and Viviani. “I refuse to yield my post to Millerand, I refuse to do you the pleasure of resigning, I refuse to become a Minister without Portfolio.” If they wanted to get rid of him after the “crushing labor” he had sustained in the last month, then the whole government would have to resign, and in that case, he said, “I have an officer’s rank in the Army and a Mobilization order in my pocket. I shall go to the front.” No persuasion availed. The government was forced to resign and was reconstituted next day. Millerand, Delcassé, Briand, Alexandre Ribot, and two new socialist ministers replaced five former members, including Messimy. He departed as a major to join Dubail’s army and to serve at the front until 1918, rising to general of division.

In Tuchman’s account, refusal to obey orders was rampant in the French army, from the Minister of War down to the lowliest private, but was frequently found as well in the British and Russian armies. As in Tolstoy’s version of Napoleon’s 1812 invasion of Russia, Tuchman tells of continual miscommunication that, added to chronic failures of military discipline, leaves one persistent impression of the opening weeks of World War I, on all fronts: utter confusion.

Essential vocabulary in the Age of Trump

Pessimistic prediction

Check back in late 2026 to see how this holds up:

- Trump’s fascist ICE raids, his trashing of government agencies, and his Neanderthal bullying foreign-policy initiatives will prove quite popular.

- He will “make deals” on his tariff threats and pass another big tax cut, so the economy will begin to rebound.

- In the mid-term elections Republicans will hold the Senate for sure and possibly keep their majority in the House, too, because the Democrats are hapless.

Nothing like us

Very few people study Ancient Greece these days.

For one thing, the Greeks were terrible misogynists. They seemed always to be at war. Their politicians were mostly driven by personal ambition, and many of them were plainly corrupt.

The richest of the Greek city-states, Athens, founded its wealth on slave labour and the economic exploitation of its smaller and weaker neighbours.

And yet, out of all that mess came great art, mathematics, literature, philosophy, and even science and medicine.

The Greeks were, in short, nothing at all like us.

Addendum: Greek words that are completely irrelevant today:

Misogyny, democracy, oligarchy, plutocracy, autocracy, demagogue, sophistry . . . well, you get the idea.

Every form of government tends to perish

Here’s more Will Durant, paraphrasing Plato’s Republic in The Story of Philosophy:

Every form of government tends to perish by excess of its basic principle. Aristocracy ruins itself by limiting too narrowly the circle within which power is confined; oligarchy ruins itself by the incautious scramble for immediate wealth. In either case the end is revolution. When revolution comes it may seem to arise from little causes and petty whims; but though it may spring from slight occasions it is the precipitate result of grave and accumulated wrongs; when a body is weakened by neglected ills, the merest exposure may bring serious disease (556). “Then democracy comes: the poor overcome their opponents, slaughtering some and banishing the rest; and give to the people an equal share of freedom and power” (557).

But even democracy ruins itself by excess—of democracy. Its basic principle is the equal right of all to hold office and determine public policy. This is at first glance a delightful arrangement; it becomes disastrous because the people are not properly equipped by education to select the best rulers and the wisest courses (588). “As to the people they have no understanding, and only repeat what their rulers are pleased to tell them” (Protagoras, 317); to get a doctrine accepted or rejected it is only necessary to have it praised or ridiculed in a popular play (a hit, no doubt, at Aristophanes, whose comedies attacked almost every new idea). Mob-rule is a rough sea for the ship of state to ride; every wind of oratory stirs up the waters and deflects the course. The upshot of such a democracy is tyranny or autocracy; the crowd so loves flattery, it is so “hungry for honey,” that at last the wiliest and most unscrupulous flatterer, calling himself the “protector of the people” rises to supreme power (565). (Consider the history of Rome.)

The lust for the spoils of office

From the “Plus ça change” Dept—

Will Durant, in The Story of Philosophy, paraphrasing Plato’s Republic:

[After describing a rural paradise of simple, healthy, peaceful life] he passes quietly on to the question, Why is it that such a simple paradise as he has described never comes?—why is it that these Utopias never arrive upon the map?

He answers, because of greed and luxury. Men are not content with a simple life: they are acquisitive, ambitious, competitive, and jealous; they soon tire of what they have, and pine for what they have not; and they seldom desire anything unless it belongs to others. The result is the encroachment of one group upon the territory of another, the rivalry of groups for the resources of the soil, and then war. Trade and finance develop, and bring new class-divisions. “Any ordinary city is in fact two cities, one the city of the poor, the other of the rich, each at war with the other; and in either division there are smaller ones—you would make a great mistake if you treated them as single states” (423). A mercantile bourgeoisie arises, whose members seek social position through wealth and conspicuous consumption: “they will spend large sums of money on their wives” (548). These changes in the distribution of wealth produce political changes: as the wealth of the merchant over-reaches that of the land-owner, aristocracy gives way to a plutocratic oligarchy—wealthy traders and bankers rule the state. Then statesmanship, which is the coordination of social forces and the adjustment of policy to growth, is replaced by politics, which is the strategy of party and the lust for the spoils of office.

Oligarchy, the anti-democratic sentiments of the wealthy classes, and the rise of authoritarian leaders: 2025? 1930? Try the 5th century B.C.E.

Yes, history keeps rhyming, and yes, the more things change the more they stay the same. Here is Will Durant setting the stage for the teachings of Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle:

[As for the Sophists,] there is hardly a problem or a solution in our current philosophy of mind and conduct which they did not realize and discuss. . . . In politics they divided into two schools. One, like Rousseau, argued that nature is good, and civilization bad; that by nature all men are equal, becoming unequal only by class-made institutions; and that law is an invention of the strong to chain and rule the weak. Another school, like Nietzsche, claimed that nature is beyond good and evil; that by nature all men are unequal; that morality is an invention of the weak to limit and deter the strong; that power is the supreme virtue, and the supreme desire of man; and that of all forms of government the wisest and most natural is aristocracy.

No doubt this attack on democracy reflected the rise of a wealthy minority at Athens which called itself the Oligarchical Party, and denounced democracy as an incompetent sham. . . . The Athenian oligarchic party, led by Critias, advocated the abandonment of democracy on the score of its inefficiency in war, and secretly lauded the aristocratic government of Sparta. Many of the oligarchic leaders were exiled: but when at last Athens [was defeated in the Peloponnesian War], one of the peace conditions imposed by Sparta was the recall of these exiled aristocrats. They had hardly returned when, with Critias at their head, they declared a rich man’s revolution against the “democratic” party that had ruled during the disastrous war.

—From The Story of Philosophy, by Will Durant

The Harlem “Renaissance”

In 1927, there were perhaps 300.000 African Americans living in the vicinity of Fifth and Seventh Avenues, roughly from 130th to 155th Streets. They lived, according to census and Urban League studies of the period, in housing designed for 16,000. . . . Many lived in tenements so “unspeakable” and “incredible,” in the words of a 1927 city housing commission report, “the state would not allow cows to live in some of these apartments.”

—Black and Blue: The Life and Lyrics of Andy Razaf, by Barry Singer

“Spinoza: A Life,” by Steven Nadler

This is an excellent biography of an extraordinary man. Benedict Spinoza, a lapsed Jew excommunicated by his synagogue and living in a Holland rancorously divided between Calvinists and Catholics, republicans and monarchists, was far ahead of his time. Even the most liberal of his contemporaries could not stomach his sceptical views of religion. The only major work that he published (anonymously) in his lifetime made him the target of vicious attacks, to the point that his grand opus, the Ethics, was published only after his death. Besides being brilliant, Spinoza lived very modestly, never sought public attention, and was known for his kindness and even temper. He died young of a respiratory illness exacerbated by years of grinding lenses and inhaling glass dust, but he may have been lucky to die when he did. Just five years before his death in 1677, the De Witt brothers, Jan and Cornelis, were beaten to death by an angry mob that stripped them naked, mutilated their bodies, and hung them up by their heels. Spinoza’s insistence on logic and reason put him at odds with his own age, and indeed with almost any place or time, and it is not hard to imagine him becoming another victim of the mob. I wish I could have met him, and shook his hand . . . and warned him about inhaling glass dust.

Robert Graves, “Good-bye to All That” (1929, 1957)

Robert Graves, born in England in 1895, enlisted as a second lieutenant in August 1914, rising to the rank of captain by October 1915. He was badly wounded at the Battle of the Somme (July to November, 1916). He was expected to die but, sent back to England, he recovered. He nearly died again in the flu epidemic of 1918.

He went on to become one of the most notable and controversial writers of the twentieth century: critic, poet, novelist, and memoirist. In 1921 Graves and his wife moved to a village outside of Oxford.

. . . The Rector . . . asked me to speak . . . at a War Memorial service. He suggested that I should read war-poems. But instead of Rupert Brooke on the glorious dead, I read some of the more painful poems by [Siegfried] Sassoon and Wilfred Owen about men dying from gas-poisoning, and about buttocks of corpses bulging from the mud. I also suggested that the men who had died . . . were not particularly virtuous or particularly wicked, but just average soldiers, and that the survivors should thank God they were alive, and do their best to avoid wars in the future. Though [some in the audience] professed to be scandalized, the ex-service men had not been too well treated on their return, and liked to be told that they stood on equal terms with the glorious dead. They were modest men: I noticed that, though respecting the King’s [request that they] wear their campaign medals on this occasion, they kept them buttoned up inside their coats.

Amen! But let’s hope we have not been “doing our best” in the last century to avoid future wars . . . . If we have, then God help us.

Plus ça change . . . (Nostradamus edition)

1789:

Among all the possible causes for the French Revolution that historians have proposed over the past two centuries, three stand out. First, the financial irresponsibility of Louis XVI severely limited his options when the crisis arrived. Second, the French nobility, blinded by their arrogance, failed utterly to understand that a few short-term accommodations might, in the long-run, preserve their status. Third, a series of droughts and other agricultural disasters pushed the country from a general depression into a disastrous situation in which thousands faced ruin and starvation, while the government failed to take any useful action. Other factors may have played a role, but these three seem sufficient to explain the cataclysmic events of 1789.

2025:

Among all the possible causes for the collapse of the Fifth Republic, three stand out. First, the financial irresponsibility of several successive governments severely limited President Macron’s options when the crisis arrived. Second, the French elite, blinded by their arrogance, failed utterly to understand that substantive change was required. Third, the COVID-19 pandemic combined with the impacts of climate change to prolong a dismal economic situation, while the government failed to take any useful action. Other factors may have played a role, but these three seem sufficient to explain the cataclysmic events of 2025.

The Magic Mountain, then and now

Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain (1924) stands at the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th as Dante’s Divine Comedy stands at the end of the Middle Ages and the beginning of the Renaissance. The threadbare plot is merely a framework within which Mann’s characters can indulge in long undergraduate arguments (“undergraduate” because of their enthusiasm, but undergraduate at a very high level—Oxford or Cambridge, for example) about history and philosophy, and his narrator can linger, endlessly it seems, over the minute details of weather, landscape, a lady’s dress, or Hans Castorp’s intricate thoughts and feelings. The history and philosophy debates sum up the Western tradition to that point—Greeks, Hebrews, Romans, Christianity, the Enlightenment, Romanticism, and the bourgeois anxieties of the 19th century—while somehow anticipating the insanities of the 20th century in which, as Mann foresaw, the brutalities of far-left ideologies would be matched blow-for-blow by the brutalities of far-right ideologies. There is more than a whiff of Dostoyevsky, too, blowing through Mann’s tuberculosis resort, both in the violent oscillations of the arguments and in the dark forebodings of the future. The Karamazov brothers would fit right in with the hypersensitive patients of The Magic Mountain. Inevitably, the novel includes an evening séance, but without a ouija board or certified Theosophist in attendance. These pampered folk, perpetually bored, search for entertainment just as their progeny do, three or four generations later. The only artists among them are dilettantes. The only intellectuals, Settembrini and Naphta, talk and talk and talk, without effect, until their comic-opera duel and the symbolic suicide of the Jesuit Bolshevik, Naphta. The fecklessness of the Magic Mountain’s inhabitants mirrors that of Chekhov’s Three Sisters (1901); the pointlessness of their lives, that of Beckett’s Waiting for Godot (1953).

The scoundrels, criminals, gangsters, and swindlers who actually make things happen never appear on the Magic Mountain. They are down below, cooking up the catastrophe we call World War I. A century later, what has changed, essentially?

The failure of the Left

The left-of-centre parties in Western democracies are failing because both their economic policies and their social policies have alienated the majority of middle-class voters.

By embracing globalization and deregulation of financial markets they have spiked the income- and wealth-gaps, leaving the middle class, at best, treading water; more usually, actually losing wealth and income against inflation; and at worst, jobless and unemployable after the export of manufacturing jobs to developing economies overseas.

At the same time they have adopted increasingly marginal social policy reforms that have alienated many voters, generated backlash, and left the minority groups they aimed to help little better off than before. The two trends go together, of course: economic resentments feed social resentments, and vice versa.

Meanwhile the upper-class elites of the Left have been padding their stock portfolios, planning their next exotic holiday travel, and hobnobbing with celebrities at gala dinners. The geniuses who championed globalization seemed utterly oblivious to the families thrown into poverty by the closure of factories. All they noticed, apparently, was the cleaner air and water. They have allowed public education to flounder for generations, while sending their own children to private schools. They have failed to lift marginalized communities—indigenous people, immigrants, people of colour—out of endemic poverty, while they and their families live in posh suburban communities equipped with parks, recreation facilities, and state-of-the-art security systems.

These failures have produced apathy among marginalized minorities, along with a majority population dominated by low-information, low-skilled citizens ready to welcome populist demagogues and vote for them—and decidedly not ready to listen to well-reasoned policy discussions by guys in $500 suits who seem to know nothing at all about the way most people are living. The populist demagogue in the $500 suit who sounds like he is just as pissed off as they are seems a better bet.

And that’s the way it is, as Walter Cronkite used to say, in December 2024.

The Canada Post strike

As Adam King has explained in his article in The Conversation, here—

—the strike by Canada Post workers results largely from the proliferation of “gig economy” businesses that to date have successfully evaded the usual requirements to pay their workers properly, provide benefits, and allow them to unionize.

The government needs to regulate these businesses and force them to treat their employees properly instead of pauperizing them by calling them “independent contractors” and thereby dragging down the entire system of social welfare that generations have fought so hard to establish.

I strongly support the Canada Post strikers, and I urge both federal and provincial governments to take action immediately to end the exploitative practices of “gig economy” businesses.

500 years, two technologies, similar chaos

1520s

In Germany, respect for traditional authority figures—the Pope, the Emperor, and other nobles—has broken down under an assault led by Martin Luther. Into that vacuum of authority hundreds of voices arise, each contending with the other. The vicious attacks made initially against the Pope are now turned by various Protestant factions against other Protestant factions, with verbal violence more than occasionally turning into physical violence. No one, including Luther himself, is excluded from the most extreme accusations and absurd slanders. All this vitriol is spread by a new technology—the printing press—which accelerates the spread of lies, rumours, calumnies, and hysteria of every sort. Where before there was one truth, now there are hundreds of truths, or none at all.

2020s

Throughout the West, respect for traditional authority figures has broken down. Ten thousand voices contend, with the same accusations—traitor! racist! fascist! etc.—hurled by opposing factions at each other. Verbal violence more than occasionally turns into physical violence. No public figure is excluded from the most extreme accusations and absurd slanders, and even private persons are not safe from attack. A new technology—social media—accelerates the spread of lies, rumours, calumnies, and hysteria of every sort. Where before there was a rough standard for establishing the truth, now there are hundreds of truths, or none at all, and no agreed standard for judging.

The authorities who lost control in each of these cases were different, of course. In the first case, the corruptions of the Papacy in Rome and the Church in general are well-known: ersatz “indulgences” and relics foisted on an ignorant populace and used to raise funds; scandalous personal behaviour and extravagant expenditures by popes, cardinals, and their monarchical retinues; and bad behaviour in local areas by priests, monks, friars, and nuns who were ill-suited to a religious vocation. Such criticisms were well-known, and had been documented by writers like Chaucer a hundred years earlier, but it was Luther who brought things to a crisis with his defiance of Rome and the Pope’s excommunication. The nobility, meanwhile, were doing their usual work of soaking the peasantry while they lived in luxury. Five centuries later in the post-WWII West, the orthodoxies that would be overthrown were more diffuse: a media elite who dominated a largely centralized system of major newspapers and major TV and radio networks; a political elite who worked hand-in-hand with this media elite; and a general agreement that some form of capitalism (with a larger welfare state favoured by the centre-left and a smaller one favoured by the centre-right) would lead to prosperity and progress for almost everyone. These orthodoxies and their representatives began to lose credibility in the 1980s when a “globalized” economy featuring free-trade agreements, fewer regulations of the financial system, and the exportation of manufacturing and heavy industries to developing countries where labour was much cheaper. The result was the rise of a new billionaire class whose wealth was generated by manipulation of financial instruments like hedge funds, while the middle and working classes saw their income and wealth stagnating or falling. These trends were only exacerbated by the rise of internet billionaires around the turn of the century. Despite their policy differences, all the mainstream political parties participated in this massive shift of wealth.

In both cases, the peasants (16th century) and the working-class (21st century) rose up in revolt, with violence in the earlier period (the Peasants’ War) exceeding—so far—violence in our own time (the truckers’ protests, the jaunes gilets in France, the January 6th attack on the Capitol in 2021). These revolts against the elites spilled over into attacks on other perceived enemies like the Jews (16th century) and the Jews and the immigrants (21st century). (The 21st century movements of immigrants into the prosperous nations of Europe and North America were impelled, of course, by that same “globalized” economy that led to soaring wealth and income gaps, job losses, and economic stagnation in Europe and North America.) In both cases, too, the earlier proponents of change (Luther, Reagan Republicans) were pushed aside by more radical voices. As in the French, Russian, and Chinese Revolutions, yesterday’s revolutionaries became today’s counter-revolutionaries and enemies of the people. The fanaticism set in motion by Luther led to the Wars of Religion in France (1562 – 1598) and the Thirty Years’ War (1618 – 1648).

The loathing between Catholics and Protestants, and between nations, was so great that when the antagonists finally agreed to negotiate it took five years to bring the carnage to an end. The Peace of Westphalia, signed on October 24th, 1648, ended more than a century of religion-stoked violence dating back to the first executions of Luther’s followers in the Netherlands in the early 1520s. The fanaticism and savagery set off by the Reformation had led to the dispossession, maiming, execution, and slaughter of millions of people. . . .

“I have often wondered,” Spinoza observed Erasmically in his Preface [to his Tractatus Theologico-Politicus (1670)], that persons who make a boast of professing the Christian religion should quarrel with such rancorous animosity and daily display towards one another such bitter hatred.”

—Michael Massing, Fatal Discord: Erasmus, Luther, and the Fight for the Western Mind

(Note 1: It is also arguable that Luther’s violent attacks and slanderous accusations against the Jews embedded anti-Jewish hatred in German culture in a particular way that made Germany the birthplace of the Holocaust four centuries later. Note 2: That “religion-stoked violence” ended in 1648 seems a highly dubious claim. Note 3: When I lived in Morocco in the 1980s I often heard that Islam, its theology rooted in the Middle Ages, needed a “Protestant Revolution.” I assume that the “slaughter of millions of people” was not included in this proposal.)

It is tempting (as always, given the limited perspective of a single human lifetime) to see the 1520s and 202s as separate cases. I prefer to see them as parts of the same story, in which civilization undergoes periodic corrections or adjustments—diastolic / systolic alternations—either when the established order’s corruption becomes unbearably oppressive, or when the chaos has gone on too long and most people are willing to give up some freedoms in exchange for peace, order, and stability.

My question: Is this process simply an endless oscillation, similar to the Greeks’ idea of a repeating move from monarchy to tyranny to oligarchy to democracy and back again? Or are we making slow progress toward a society in which both the oppressive inclinations of elites and the violent reactions of the masses are contained within some kind of acceptable range?

It’s the same old song . . .

Summarized from Jazz on the River, by William Howland Kenney (2005), pp. 107-108:

- 1896: The American Federation of Musicians is founded with forty-four local unions. Local #44 is the Black musicians’ union in St. Louis, Missouri. For three decades Local 44 prospers, with Black musicians playing the venues that white musicians didn’t want: dance halls, nightclubs, and riverboats.

- 1927: With the end of silent movies, the white musicians who formerly played in movie theatres lose those jobs and begin moving in on the riverboat jobs, throwing Black musicians out of work.

- 1929: With the Depression, white musicians lose most of their other jobs playing vaudeville, stage shows, opera houses, and concert halls.

- 1930: The A.F.M. revokes Local 44’s charter, making it impossible for Black musicians to negotiate for contracts playing on the riverboats. Subsequently, three-quarters of the remaining riverboat jobs go to white musicians, leaving most Black musicians playing in marginal venues for non-union wages. Similar stories played out in cities across the nation.

- 1944: the A.F.M. finally charters a new union for Black musicians in St. Louis, Local 197.

- 1971: Local 197 is dissolved when the St. Louis musicians’ union is finally integrated.

November 2024

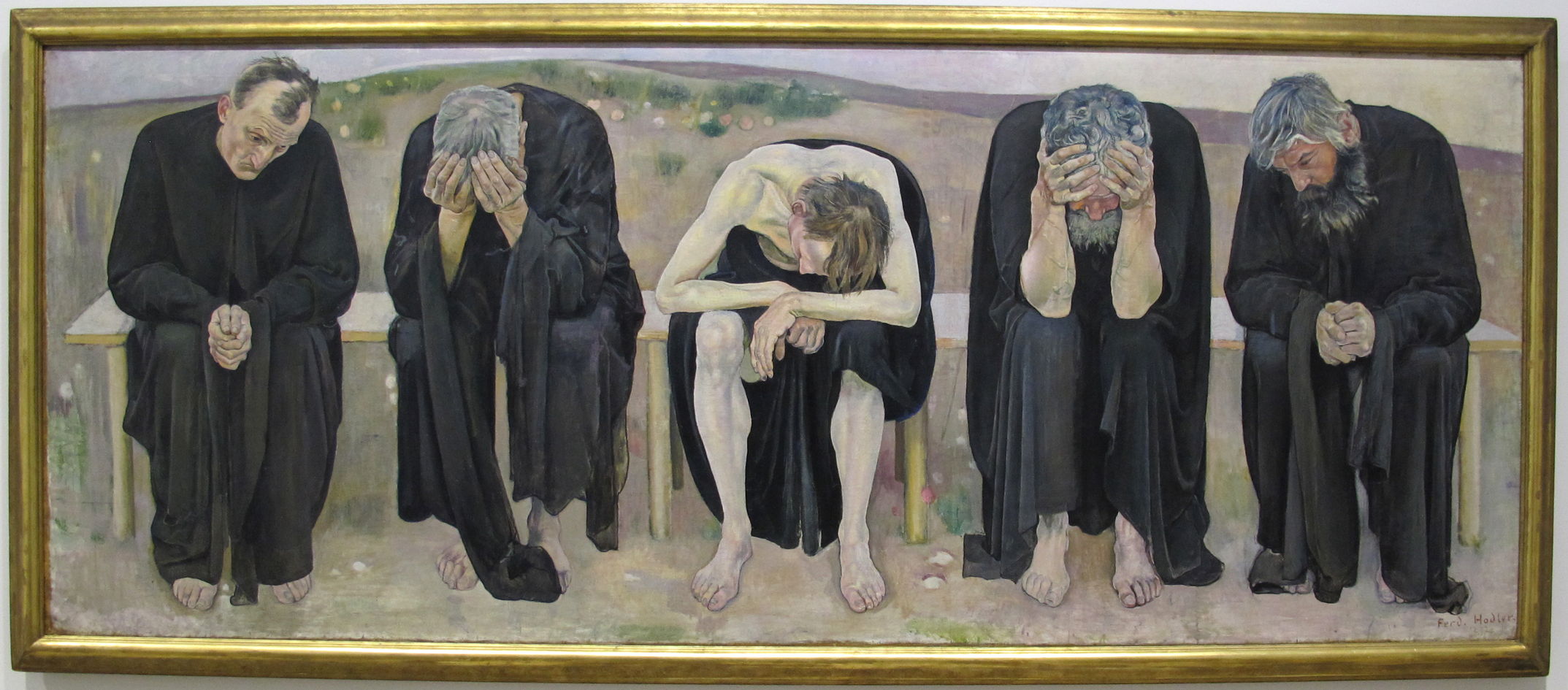

To be hopeful in bad times is not just foolishly romantic. It is based on the fact that human history is a history not only of cruelty, but also of compassion, sacrifice, courage, kindness. What we choose to emphasize in this complex history will determine our lives. If we see only the worst, it destroys our capacity to do something. If we remember those times and places — and there are so many — where people have behaved magnificently, this gives us the energy to act, and at least the possibility of sending this spinning top of a world in a different direction. And if we do act, in however small a way, we don’t have to wait for some grand utopian future. The future is an infinite succession of presents, and to live now as we think human beings should live, in defiance of all that is bad around us, is itself a marvelous victory. . . .

Whenever I become discouraged (which is on alternate Tuesdays, between three and four) I lift my spirits by remembering: The artists are on our side! I mean those poets and painters, singers and musicians, novelists and playwrights who speak to the world in a way that is impervious to assault because they wage the battle for justice in a sphere which is unreachable by the dullness of ordinary political discourse.

—Howard Zinn,

from A Power Governments Cannot Suppress and “Artists of Resistance”

Clown, madman, thug: the appeal of fascism

Hitler’s power and success never ceased to astonish Mussolini. There was something unreal, something that didn’t make sense about the triumph of this Bohemian psychopath. In his heart of hearts, Mussolini saw Hitler’s success as a bizarre freak, an aberration on the part of world history. . . .

Novikov . . . [after seeing a Nazi army officer on the street] said to himself three words he would remember again and again. “Clown!” Then correcting himself: “Madman!” Then correcting himself once more: “Thug!”

—Stalingrad, by Vasily Grossman (1952)

Hitler, Hinkel, Drumpf, Trump: variations on a theme. Why does the fascist clown madman thug appeal to millions of people? All our astonishing science and technology will mean nothing if we cannot answer this question and put fascism finally, permanently in the past.

Even the best army . . .

Even the best army is doomed to fail when it is required to perform impossible tasks, that is, when it is ordered to campaign against the national existence of other peoples.

—General Friedrich Paulus, commander of the German 6th army who surrendered to the Russians in the Battle of Stalingrad.

Perhaps Vlad Putin and Bibi Netanyahu should take note.

Hurricane Trump: The climate has changed

Meteorologists are scrambling to make sense of the what experts call the most dangerous instance of bizarre weather events seen so far.

“The climate isn’t changing,” one of them says. “It has changed.”

Hurricane Trump, readers may recall, seemed to have finally disappeared in early 2021. “We thought the worst was over then,” says Dr. Jeremiah Sunshine, head of the National Hurricane Center.

Now, however, to the experts’ amazement, Hurricane Trump has returned and is heading not for a particular city or region, but straight towards the entire United States! Hurricane watchers say that unless Trump changes course at the last minute, it will wipe out much of the US and then head straight for Western Europe. Only Moscow, Pyongyang, and Budapest would appear to be safe. They are calling this incredible phenomenon “Hurricane Trump II.”

Hurricane Trump first appeared in 2015 in New York City. Veering southward, it struck Washington, D.C., inflicting what commentators kept calling “unprecedented” damage. Environmental regulations were blown to pieces, while corporate profits soared out of sight. The federal budget exploded, and the national debt disappeared into the stratosphere along with corporate profits. The Republican Party took a direct hit, and has been out of commission ever since. International allies were battered mercilessly, while adversaries, strangely, seemed to sail serenely through the chaos. In the midst of all this, the COVID-19 pandemic threw everything into a confusion that was made even worse by Hurricane Trump, which spewed denials, bleach, and horse pills in every direction while bodies piled up in temporary storage trucks and hospitals were overwhelmed by the number of patients and the lack of essential supplies. Hurricane Trump continued throughout the 2020 election year and into 2021, when it smacked right into the US Capitol on January 6th. The resulting injuries, deaths, broken windows, pilfering, and filth seemed to mark the climactic end of the storm, and despite all the damage there was a widespread feeling that the ordeal was finally over.

The reappearance of Hurricane Trump three years later cannot be accounted for. Climate scientists are reconfiguring their models and projections, trying to understand a new reality in which hurricanes, long after they appear to be over, return like boomerangs, stronger than ever. “I am sorry to say that we have little understanding of what is happening,” says Dr. Sunshine. “We can only advise people to board up their windows, pile up the sandbags, avoid pregnancy or any other condition requiring gynecological care, try not to be an immigrant or even to look like one, fill up the gas tank, and be ready to flee at a moment’s notice.” Asked if anything else can be done, Dr. Sunshine paused thoughtfully. “Well,” he said, “it couldn’t hurt to vote. Might not help, but it couldn’t hurt. At this point, it’s certainly worth a try.”

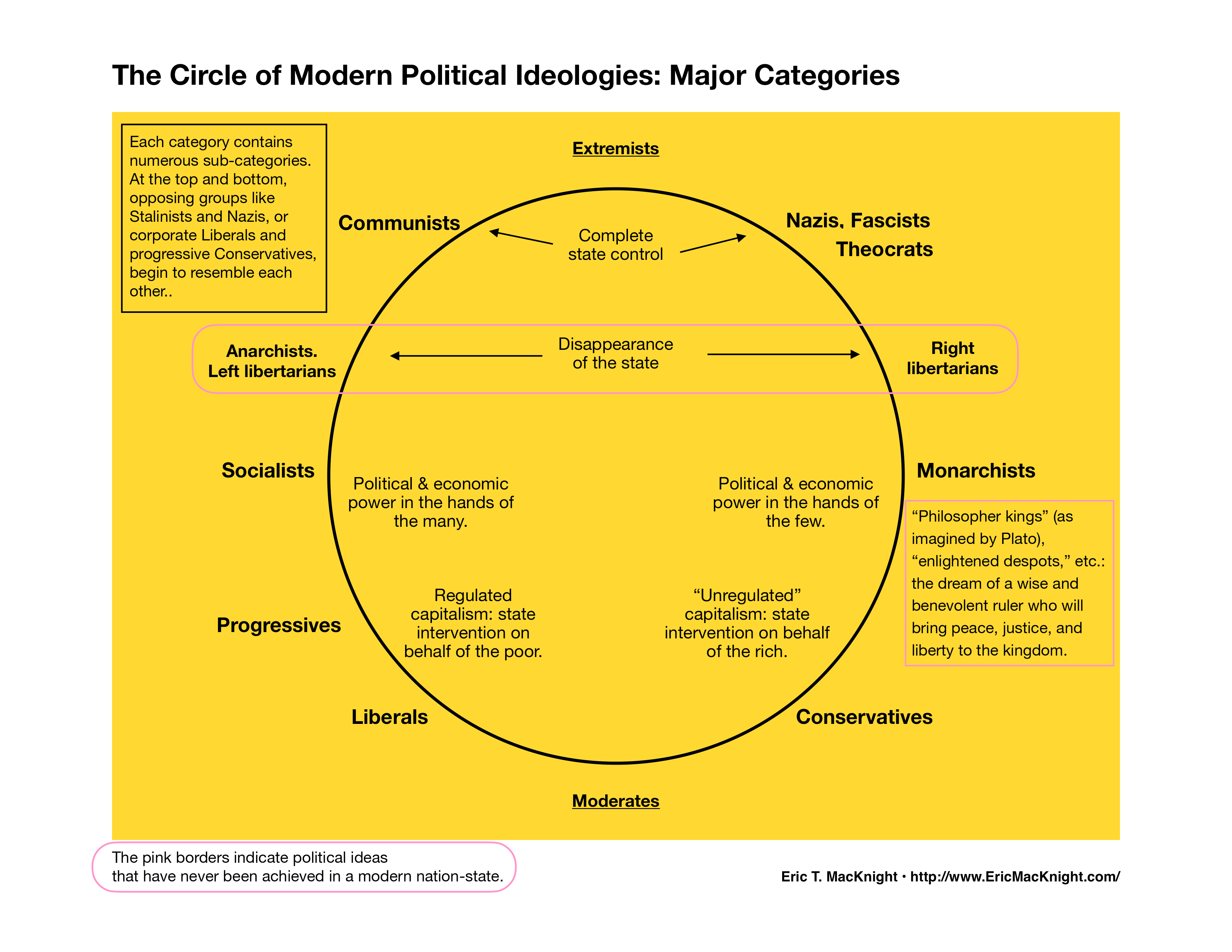

The Circle of Modern Political Ideologies

It’s not a line, or spectrum, from right to left, but a circle where the extremes meet at the top and the moderates mush together at the bottom. Understood in this way, things begin to make sense: the love affair of the American far-right with Putin of Russia and Kim Jong Un of North Korea, and Mr. Trump’s mish-mash of name-calling against his enemies, and the difficulty distinguishing between “corporate liberals” and “moderate conservatives,” for example.

Toxic Globalization: guns, drugs, oil, and music

Bread and circuses, my eye. Those Romans were amateurs.

Globalization began with Silk Road traders bringing bubonic plague to Europe, wiping out a third of the population.

It continued with Columbus and other Europeans bringing a catastrophic pandemic to the Americas in exchange for gold, silver, tobacco, tomatoes, and potatoes.

It reached a new high with the British triangle trade: guns and cotton fabric to West Africa in exchange for slaves who were taken to Caribbean and American colonies to work on sugar plantations and, later, cotton plantations. Sugar, rum, cotton—and lumber for shipbuilding—went from the colonies to Great Britain, completing the triangle.

Sugar was needed for the tea to which Britons had become addicted. The tea came from China, and as the Chinese wanted nothing British except silver, which the Brits did not want to part with, a two-pronged solution was conceived. First, they exported opium from another British colony, India (which included what we now call Afghanistan) to China and bullied the Chinese into trading tea for opium, eventually addicting millions of Chinese. Second, they stole the secrets of processing the leaves of Camellia sinensis into tea, and then developed tea plantations of their own in India and Ceylon (now called Sri Lanka).

In the 20th century, especially after World War II, globalization expanded. All those factories built to make weapons for the war needed new markets. Guns went to “developing” countries, i.e., former European colonies in Africa and Asia and Latin America; in return came illegal drugs to feed the growing addiction market in Europe and North America: marijuana, cocaine, and our old friend opium, now refined into heroin. The third major commodity of world trade was petroleum, without which international trade would have been much slower—petroleum, which literally fuelled automobile culture, the international travel industry, and the global environmental crisis.

Indispensable to all this commerce were bankers and gangsters.

Organized crime works by skimming profits, and globalization provided unprecedented business opportunities. Dictators and insurgents around the world needed weapons; gangsters could provide them, even where the commerce was prohibited by law. Weapons were often exchanged for drugs that could be exported and re-sold at enormous profits, using the clandestine networks developed by the gangsters. The dirty money acquired in these transactions needed to be cleaned (“laundered”) and that’s where bankers, casinos, and real estate developers came in.

In the United States, the sale of alcohol was made illegal in 1920. Prohibition led to an explosion of organized crime. Big money could be made running illegal breweries, distilleries, bars, and nightclubs, and importing alcohol from outside the country. During the Great War of 1914-1918, another wave of the Great Migration had swelled Black urban populations in the northern cities where factories churned out war matériel. They brought their music with them: gospel music, blues, ragtime, and jazz. An economic boom followed World War I. Urban populations had money to spend. Organized criminals supplied the music and the booze. At the same time, technology enabled recordings that could be distributed nationwide—and beyond—and radio broadcasts sent the new music into almost every home. Entertainment and music became industries controlled by organized crime. Musicians were kept in poverty by nightclub owners and record companies that skimmed most of the profits for themselves.

In Chicago, Al Capone adored the music and fostered an entire generation of music. In Harlem, the Mob-owned Cotton Club had as its house band the sophisticated Duke Ellington Orchestra. Kansas City had an entire district of jazz clubs . . . made possible by a corrupt political machine that served as a model for the Havana Mob [of the 1950s] as constructed by [the gangster Meyer] Lansky, [Cuban dictator Fulgencia] Batista, et al.

—T. J. English, Havana Nocturne, p. 244

After Prohibition ended in 1933, many of the gangsters switched to drugs: marijuana, cocaine, and heroin. (Others, most notably Meyer Lansky, disliked the drug trade and instead moved most of their operations to the casino business in Cuba.) Musicians were often paid in drugs, and their addictions provided a new market for the drugs being imported by the mafia while also ensuring that the musicians would remain dependent.

Musicians unwilling to perform and record on the gangsters’ terms simply could not work. Behind the scenes of almost any star singer, musician, band, or comedian you will find the mafia. Louis Armstrong hired a mobster, Joe Glaser, to be his manager, knowing that Glaser would enrich himself at Armstrong’s expense. Why? Because Glaser would protect him. Forty years later, five young men who later came to be known as The Band could not get a recording contract from anyone except the mobster Morris Levy; faced with the choice of getting ripped off or not recording at all, they signed with Levy. Such famous cases are not extraordinary—they are typical. The mob’s control of the “entertainment industry” was pervasive.

[1931, Chicago] By this time he had his big ‘Pistol—Pulling it out—As he said—”My name is ‘Frankie Foster.” And he said he was sent over to my place (Show Boat) to see that I ‘Catch the first train out to ‘New York. . . . Then He Flashed his Big ‘Ol’ Pistol and ‘Aimed it ‘Straight at ‘me. With my ‘eyes as big as ‘Saucers’ and ‘frightened too I said—”Well ‘Maybe I ‘Am ‘going to ‘New York.”

—Louis Armstrong in His Own Words, p. 110

Instead of going to New York, Armstrong fled. He spent two years in Europe. When he returned, he hired Joe Glaser to be his manager, following the advice given to him by a friend when he left New Orleans:

[Black Benny] said (to me), “Dipper, As long as you live, no matter where you may be—always have a White Man (who like[s] you) and can + will put his Hand on your shoulder and say—“This is “My” Nigger” and, Can’t Nobody Harm’ Ya.”

There was a positive side to these relationships. Both Jews and Italians had been the victims of prejudice as immigrants, and neither group had quite the same racist aversions to Blacks as did the White Anglo-Saxon Protestant majority. Among many of these Italian and Jewish gangsters, Black musicians found protectors who shielded them from racist patrons and cops, bailed them out of jail, gave them a meal or a drink when they were down and out, or paid their rent, and employed them. There was also a significant number of Italian and Jewish performers—singers, comedians, musicians—who shared stages with Blacks and became friends, breaking the taboos of racism and leading the way toward a future of equality and justice. Overall, however, all performers were exploited by the gangsters, and white gangsters were just as racist as other whites.

In 1950s Cuba, Havana’s casinos, nightclubs, and brothels were mob operations that financed the Batista dictatorship. Hollywood movie stars, politicians like the young John Kennedy, along with many other celebrities and high-flyers provided a glamorous cover for this sordid arrangement. When the Castro revolution expelled the mob from Cuba, they retrenched to Las Vegas’s garish casinos and hotels, where middle-class Americans with money to spend could “let their hair down”: gambling, strippers, big-name entertainers, and lots of alcohol.

In the 1980s, Reagan’s deregulation of banking and finance made it possible for a new class of billionaires to suck money away from the middle classes into their own bulging pockets, until the U.S. wealth gap came to resemble the traditional wealth gaps in monarchies and dictatorships: a tiny group of the super-rich at the top, and then everyone else. The difference between this deregulated hedge-fund capitalism and the “pure capitalism” of organized crime? The hedge-fund guys had purchased legislators who made their operations legal.

Long before the 1980s, there were discreet but obvious ties between the Mob and “legitimate” businessmen. Frank Sinatra’s valet, George Jacobs, recounts a holiday gathering of gangsters in Palm Springs:

And it wasn’t just Sam Giancana. Throughout the day one mob boss after another showed up at [Sinatra’s] Alejo house. There was Johnny Rosselli, . . . a guy named Joe F. and another called Johnny F, and some others with Italian names no one could pronounce. Each guy came with at least one or two thick-necked bodyguards. . . .

That weekend I would drive Sam Giancana around Palm Springs to meet his visiting fellow mobsters, each of whom was staying in some gated mansion, not of celebrities but rather of the faceless fat cats from all over who owned manufacturing companies and heavy industry . . . . Those mobsters were certainly connected, although I’m not sure to whom.

—

Mr. S: The Last Word on Frank Sinatra, by George Jacobs and William Stadiem (2003)

Drugs and alcohol, guns, oil . . . an “entertainment industry” controlled by the same criminals who trade in guns and drugs . . . a corrupted banking industry facilitating the transfer of huge amounts of money . . . billionaires in super yachts while middle-class folks struggle to buy a home or pay medical bills or finance an education beyond high school . . . pandemics spreading worldwide faster than we can even track . . . a climate crisis that threatens to make much of the planet uninhabitable.

That’s what globalization has brought us, but like the addicts we are, we tolerate all the short-term side effects and long-term debilitation in return for the highs, the sweetness, the bliss. Without globalization, would we have Louis Armstrong, Miles Davis, The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, etc.? Would we have Olympic champions, the World Cup, the World Series, the Super Bowl, and all the amazing athletic achievements of the past century? Would we have dazzling holidays around the globe? Would we have restaurants serving up delicious ethnic cuisines in our home towns and “world music” on our playlists? The culture and economy spawned by globalization feed our addictions, both literal and metaphorical, and it seems inevitable that we will end up as all unreformed addicts do.

CODA

So, what are the “through lines” in this story?

- Technology, from the wheels and sailing ships that connected China to Europe in the days of the Silk Road, to the cell phones and social media that connect everyone to everyone else today.

- Genius and talent, funded by gangsters both legal and illegal. Think of the Florentine bankers who financed the Italian Renaissance, making Michelangelo and Leonardo possible; or the hedge fund billionaires who own the Los Angeles Dodgers, making Shohei Ohtani possible; or Werner von Braun, funded by Hitler, and then the US government; or the fabulous music of post-WWII Cuba, funded by the Mob’s casinos.

- Addiction. To tea, to sugar, to alcohol and other drugs. To entertainment. To gambling. To sex. To shopping. To social media. To everything.

- Environmental destruction. Coal. Petroleum. All the pesticides, herbicides, and chemical fertilizers required for industrialized agriculture. Air pollution, water pollution, soil contamination. Insect and bird populations, aquatic life, hundreds of other species extinct or in danger of extinction. All of this leading to climate change, mass migrations, and potentially making the planet uninhabitable.

- Pandemics, from the bubonic plague to smallpox and syphilis to influenza to SARS and COVID and mpox, with more to come, we are told.

- Exploitation of vulnerable populations. Of China by the British in the 18th century. Of Asia, Africa, and the Middle East by Europeans in the colonization that began with Columbus and continued for the best part of 500 years. In the “neo-colonial” economic imperialism of the Cold War era that followed decolonization and World War II, and continues today. Of women, trafficked around the world, both for sex and to labour in sweatshops where they help to feed the appetites of those who are better off for more and more things, at bargain-basement prices. Of migrants working illegally to process chickens or harvest vegetables so the rest of us can buy groceries at prices we can afford.

E. F. Schumacher, the author of Small Is Beautiful, was right. Aldous Huxley, in Brave New World, was right. Neil Postman, in Amusing Ourselves to Death, was right. But they were all, along with many others less well known, spitting in the wind of globalization. Me, too.

Further Reading

- Mezz Mezzrow, Really the Blues (1946)

- Levon Helm, This Wheel’s on Fire (2nd ed., 2000)

- The Baby Dodds Story, as told to Larry Gara (2002)

- Tony Scherman, Backbeat: Earl Palmer’s Story (1999)

- Frank Driggs and Chuck Haddix, Kansas City Jazz: From Ragtime to Bebop—A History (2005)

- Louis Armstrong in His Own Words, ed. Thomas Brothers (1999)

- T. J. English, Havana Nocturne: How the Mob Owned Cuba and Then Lost It to the Revolution (2009)

- T. J. English, Dangerous Rhythms: Jazz and the Underworld (2023)

- George Jacobs and William Stadiem, Mr. S: The Last Word on Frank Sinatra (2003)

- “BC’s Underground Economy Is Huge. And Deadly,” by Geoff Meggs. The Tyee, 22 August 2024. https://thetyee.ca/Analysis/2024/08/22/BC-Underground-Economy-Huge-Deadly/

CODA #2

Listen to the younger son of independent Singapore’s founder, Lee Kuan Yew. The Lee family has controlled Singapore, poster child for the post-WWII Asian economic “miracle,” since 1965.

“There is a need for the world to look more closely, to see Singapore’s role as that key facilitator for arms trades, for dirty money, for drug monies, crypto money.”

A Singapore government spokesperson said the country had “a robust system to deter and tackle money laundering and other illicit financial flows”, pointing to its favourable ranking in Transparency International’s corruption perception index, well above the UK.

Duncan Hames, director of policy at Transparency International UK, said: “As Britain knows all too well, countries can look like they don’t have a domestic corruption problem yet still play a key role in enabling corrupt networks elsewhere. Singapore’s regional role as a major financial hub makes it attractive to those seeking to move or hide illicit funds, especially from a relatively high-risk neighbourhood.”

COVID-19: “An ongoing threat”

Despite overwhelming evidence of the wide-ranging risks of COVID-19, a great deal of messaging suggests that it is no longer a threat to the public. Although there is no empirical evidence to back this up, this misinformation has permeated the public narrative.

The data, however, tells a different story.

COVID-19 infections continue to outnumber flu cases and lead to more hospitalization and death than the flu. COVID-19 also leads to more serious long-term health problems. Trivializing COVID-19 as an inconsequential cold or equating it with the flu does not align with reality.

State of play, mid-July 2024: we’re all in the soup. [updated]

Updated July 21—now that Biden has announced he won’t run for re-election. Buckle up for a sexist / racist hullabaloo! If the Dems unite behind Harris, they have a chance. Otherwise, it’s Project 2025 time. (See bold-faced bullet point, below.)

- Joe Biden has been the most progressive president in history and has pushed back against corporations, the super-rich, and the Israeli government (not nearly enough to satisfy anyone outraged by the genocide of Palestinians, but plenty enough to piss off the pro-Netanyahu folks (see below). He is also elderly, and a terrible public speaker, thus a) turning off a huge proportion of know-nothing voters who like their celebrities young, cool, and glib; and b) providing ample fodder for a media feeding-frenzy. Yesterday we learned that he has COVID again, which will only add to the frenzy.

- The corporate Dem crowd of billionaires who don’t want regulation or taxation of the rich any more than their right-wing MAGA billionaire brethren are trying to get rid of both Biden and Harris.

- The AIPAC pro-Israel nuts who will do anything to put a pro-Bibi president in the White House are for Trump.

- The low-information “moderates” and “independents” who will determine the outcome of the election do not like or trust Kamala Harris because she is a) a woman, and b) non-white.

- The black women voters who were essential to Biden’s razor-thin wins in swing states in 2020 will not turn out for the Democratic candidate if Harris is dumped.