In 19th-century Europe the growing middle class generated by the Industrial Revolution developed a new way of life. In bourgeois towns the streets were lit at night; policemen ensured order, supported by judges, courts, juries, and jailers. City parks provided pleasant Sunday walks, and perhaps even a brass band playing music in a pavilion. Fathers went to work each morning. Some returned home for the midday meal, along with the children home from school; all returned home for supper with the family. Mothers stayed at home to care for the children, maintain the house, and prepare the meals. In wealthier families they were assisted by servants who helped with the cooking, cleaning, shopping, and care of the children. The men worked in shops and offices, as clerks or salesmen, or as managers in one of the local factories. Physical labour was left to the working class in towns, and to farmers in the countryside. Wars were a thing of the past, or took place only at the remote edges of the continent.

In this new bourgeois society, new male stereotypes emerged: the pompous banker; the crafty lawyer; the doctor who might cure you or might kill you with his primitive treatments; the dandy, with his fancy clothes and smooth talk for the ladies; the mousy clerk; the fawning salesman. None of these male figures were strong candidates for the army. No, the army’s officers were from the upper classes—the noblemen who for countless generations had been bred for war. The ordinary soldiers and sailors were from the working classes. The bourgeois men were too soft to make good soldiers. They were peacetime creatures, better suited for commerce than for combat. Sport was the only aspect of bourgeois life where the old warlike masculine virtues were still cultivated, with boxing and wrestling most prominent. (In the 20th century the role of sport in bourgeois life exploded, with multiple forms of team sports and an entire industry of exercise and fitness for people who rarely exercised their bodies on the job.)

When it came to love and marriage, this bourgeois society produced a whole new set of stereotypes. The young bourgeois man was not very attractive to the girls whose attention went to the “bad boys” with bulging muscles and scars from brawling. These “dangerous” guys seemed much more exciting to girls than the well-behaved, well-dressed, well-spoken boys they knew from school. Despite their attractions as lovers, however, these “dangerous” men rarely made good husbands—if they married at all—and so most of the bourgeois girls eventually got over such passing infatuations and settled on some reliable fellow who could be counted on to provide her with a comfortable life and be a good husband and father. In the 20th century, similar dissatisfactions with the lack of excitement in bourgeois life led teenagers of both sexes to experiment with “wild” behaviours featuring music offensive to their parents, crazy fashions and hairstyles, tattoos, motorcycles, boyfriends or girlfriends their parents would not approve of, drug and alcohol abuse, and sexual adventures—anything and everything, in short, to violate bourgeois norms and conventions.

At the heart of this new bourgeois life and its dissatisfactions was the new bourgeois man who, despite his education and sophistication, was decidedly unexciting. The stereotypical man of earlier times, by contrast, performed physical labour that kept him fit and strong; was ready at a moment’s notice to use his fists or pick up a weapon to wield against enemies or wild beasts; but could also play a fiddle or sing a song or build a house, and wanted to marry a good woman and raise a family. He combined, in short, the traditional masculine virtues with a dedication to home and family.

These traditional masculine virtues go way, way back. In Homer’s Odyssey we hear the tale of Ares, the god of war, having an affair with Aphrodite, the goddess of love who has been married to the crippled smith god, Hephaistos, in a failed attempt to tame and domesticate her. Ares is hyper-masculine: a strong, handsome warrior who loves the battlefield even more than he loves women. Aphrodite is hyper-feminine: beautiful, sexy, and unfaithful. In bourgeois society Ares would be a low-class thug, and Aphrodite a shameless whore. Their extremes of masculinity and femininity are taboo in a middle-class world. The problems of respectable middle-class women managing their inner Aphrodites deserve attention, and the consequences of middle-class women violating sexual taboos are serious and well-known: scandal, disgrace, sexually-transmitted disease, unwanted pregnancies, abortions, single motherhood, etc. But our focus here is on the marginalization and condemnation of hyper-masculinity in bourgeois society, because the consequences of men violating bourgeois taboos around masculinity range from the personal (e.g., assaults, domestic violence, rape) to the collective (e.g., gangs, fascism, and war). We see these pathological versions of manhood today in politics and society around the world: authoritarian leaders, tribal and national chauvinism, celebration of “bro culture”; pop music stars who are misogynistic in both their art and their lives; politicians who ramp up male fear that the women are “taking over.”

In William James’s 1910 essay, “The Moral Equivalent of War,” he writes of “manly virtues,” of which he approves and wishes to preserve while at the same time avoiding their ultimate testing-ground, war. Society may have changed, James writes, but human nature remains: “modern man inherits all the innate pugnacity and all the love of glory of his ancestors.” That “love of glory” reminds us, perhaps, of sport as both preparation and substitute for war. “We are the champions!” cry the winners. Sport having failed to end war, James proposes his “moral equivalent”: mandatory conscription of all young men for a period of service dedicated to arduous tasks that are needed but usually regarded as undesirable vocations: “To coal and iron mines, to freight trains, to fishing fleets in December, to dishwashing, clothes-washing, and window-washing, to road-building and tunnel-making, to foundries and stoke-holes, and to the frames of skyscrapers, would our gilded youths be drafted off, according to their choice, to get the childishness knocked out of them . . . .” Working in teams, they would toil and sweat together, help each other, learn brotherhood and comradeship, and have the satisfaction of giving themselves to a cause greater than their own petty, personal desires. James, writing in the last year of his long life, asserts that “Such a conscription . . . would preserve in the midst of a pacific civilization the manly virtues which the military party is so afraid of seeing disappear in peace.” In closing he writes, “I have no serious doubt that [we] are capable of organizing such a moral equivalent as I have sketched, or some other just as effective for preserving manliness . . . .”

Without doubt James’s scheme would achieve a good deal, as we have seen in the United States in the Depression-era Civilian Conservation Corps, or in John F. Kennedy’s Peace Corps. These programs, however, though inspired by James’s essay, were both voluntary—the universal conscription proposed by James has never been tried. Without such an experiment, we cannot know whether James’s idea could indeed so satisfy the noble and positive aspects of war that war itself would forever end. Is it possible to tame the urge to make war? One thinks of chivalry, the medieval attempt to civilize roaming bands of armed brigands plaguing towns and cities by inspiring them to be noble, brave, honest knights upholding Christian morality and defending the weak and defenceless (especially if they were beautiful ladies). We may scoff at this chivalric myth, but it has had some staying power. Millions of young men, admonished by their mothers to behave “like gentlemen,” have learned to stand when a lady enters a room, to offer their seats to the elderly, to remove their hats at the supper table, to speak without swearing, and to defend others against bullies.

On the other hand, a few minutes spent browsing social media may lead to serious doubts about chivalry’s staying power. And while many young men may still learn good manners from their parents, it is hard to see this as more than surface behaviour that quickly evaporates under stress—or when using an encrypted account. Underneath any polite bourgeois surface that still exists, the hyper-masculine spirit of Bertran de Born (ca. 1140 – 1215), the Occitan poet-warrior, still lurks:

Maces and swords, colourful helms,

shields riven and cast aside:

these shall we see at the start of the battle,

and also many vassals struck down,

the horses of the dead and wounded running wild.

And when he enters the combat,

let every man of good lineage

think of nothing but splitting heads and hacking arms;

for it is better to die than to live in defeat.

I tell you, I find no such savour

in eating or drinking or sleeping

as when I hear the cries of “attack!”

from both sides, and the noise

of riderless horses in the shadows;

and I hear screams of “Help! Help!”

and I see great and small alike

falling into the grassy ditches

and the dead

with splintered lances, bedecked with pennons

through their sides.

—from “Be’m plai lo gais temps de pascor”

The ladies of Eleanor of Aquitaine’s court, according to the legend, invented chivalry to tame the violence of the men around them. Can we do better? Can we have manhood without murderous violence, or are the two inseparable? If humans are indeed highly evolved animals rather than aspiring angels, perhaps other animals can help with these questions. A male dog who cannot be trained out of his violent behaviour is sometimes castrated. The same procedure is used with stallions and other farm animals that are no longer needed for breeding. From the Wikipedia page on gelding:

Castration allows a male animal to be more calm, better-behaved, less sexually aggressive, and more responsive to training efforts. Additionally, it is known for making the animal quieter, gentler and generally more suitable as an everyday working animal, or even as a pet (in the case of companion animals).

A drastic solution, but apparently it works. Would it be a violation of human rights? Cruel and unusual punishment? Or a natural consequence for people whose repeated anti-social violence poses a grave threat to society? Surely there must be less drastic solutions. Are prison and castration our only options for controlling anti-social hyper-masculinity, or can men learn to express their virility in positive ways that make them better people and make their communities stronger and safer? Will future scientists devise a way to adjust the hormone levels of an anti-social male without emasculating him? Or must we expect that war and violence, as they have always been part of human experience, will remain with us as long as there are humans?

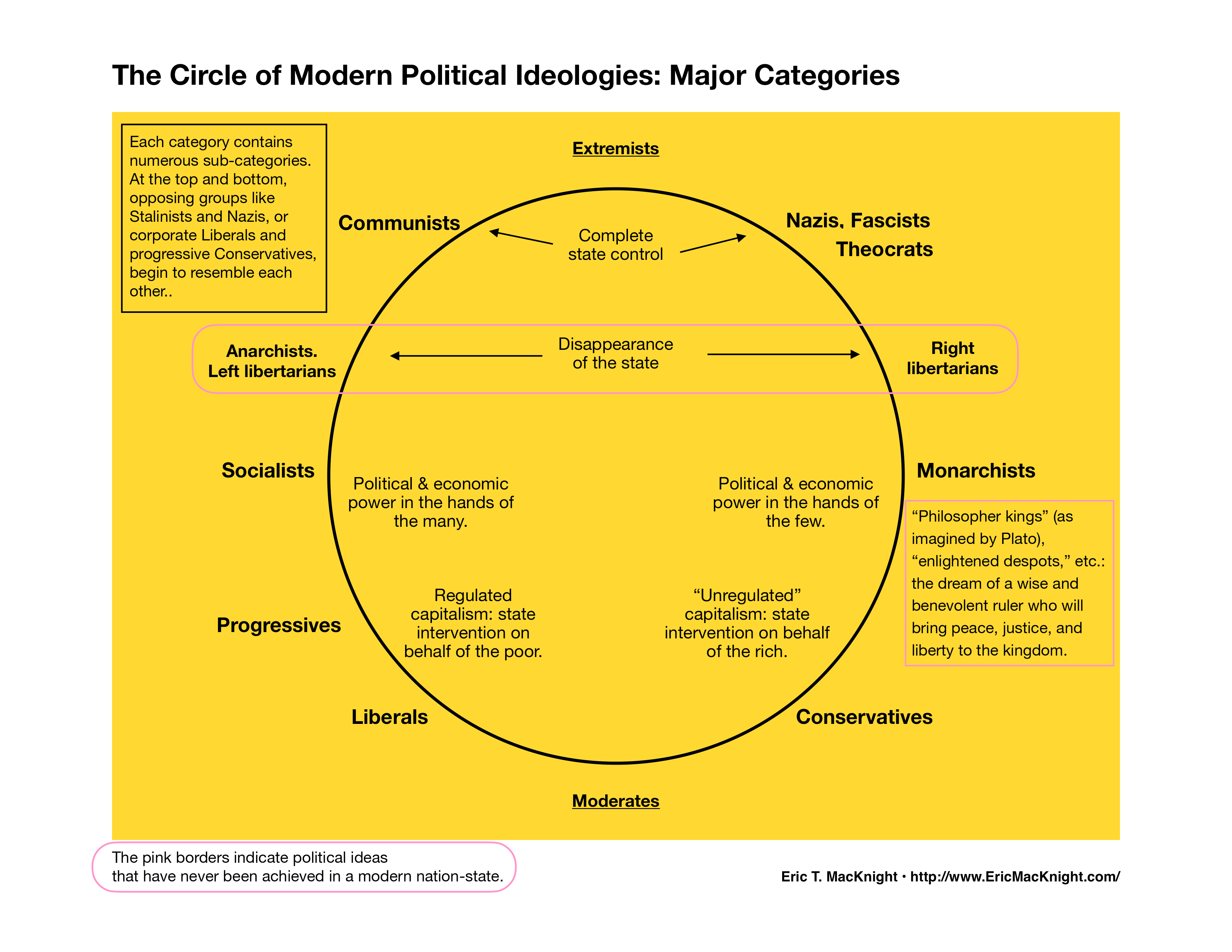

I am reminded once again of that triangular diagram of human nature, as imagined by Plato and Aristotle, and recycled by Dante in his vision of Hell. The diagram shows Appetite and Will as the base of the triangle. Reason, the highest and best part of human nature, according to the Greeks, and for Christians the most divine part of our nature—the part that distinguishes us from other animals—is the small bit at the top of the triangle. Optimists have argued that we can use our reason to restrain our appetites and master our will. Recent studies in neuroscience, however, have suggested that our choices are made long before they reach the level of articulation, and that while we may think we are using our reason to make decisions, we are actually using our reason to ratify decisions already made unconsciously. Politics and current events in the 21st century would seem to support this view, especially when one considers the perverse reasoning used to justify bigotry, hatred, discrimination, and an appalling variety of atrocities.

Dante’s Hell is this same diagram, flipped upside down. As Virgil guides the Pilgrim down into the pit of Hell, they begin with the less serious sins—sins of the appetites—pass through the sins of willfulness, and finally reach the bottom of the pit, where the worst sins are punished: those that involve perversion of Reason, that divine gift of God to humans, for evil purposes. The logic is clear, but I am beginning to think that Dante got it wrong. When I consider the most pernicious human evils—racism, religious hatred, sexism and misogyny, and the hyper-masculinity that transforms these negative emotions into murderous violence—they seem to be rooted deep in our nature, in our appetites and our willfulness, in our psycho-biology. Reason has little to do with these dark impulses. We fear the Other, a fear based in our own insecurities, and that fear easily turns to hatred. Men’s insecurities respond to threats, as discussed above, with hyper-masculine violence both individual and collective. Can we be kind, loving, generous, even selfless? Of course . . . but only, it seems, if we have been blessed with situations in which our insecurities are not threatened. Here is Hamlet’s take:

What a piece of work is a man! How noble in reason! how infinite in faculty! in form, in moving, how express and admirable! in action how like an angel! in apprehension how like a god! the beauty of the world! the paragon of animals! And yet, to me, what is this quintessence of dust? . . .

Use every man after his desert, and who should ‘scape whipping?

—II.ii

Ah, but Hamlet, as we know, was prone to melancholy.