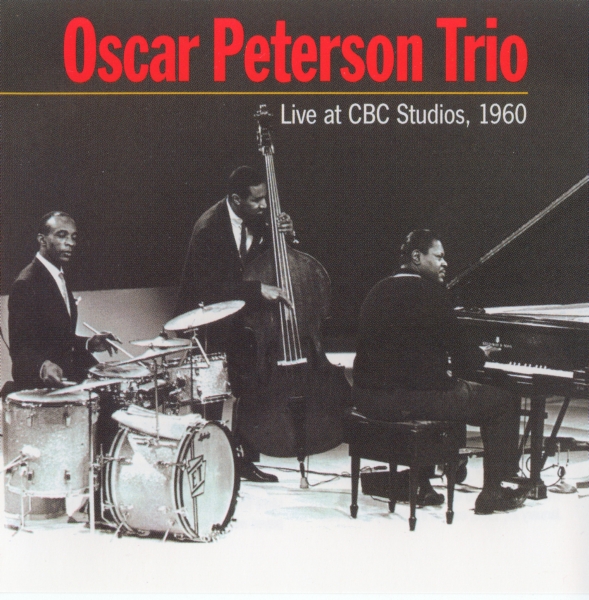

With the elegant Ray Brown on bass and Ed Thigpen on drums. Check out Thigpen’s classic Ludwig kit.

Teaching, reading, good habits, and more

With the elegant Ray Brown on bass and Ed Thigpen on drums. Check out Thigpen’s classic Ludwig kit.

The sun came out for Canada Day, and it was glorious.

N.B. I chose the seaside, not Quebec (read the green sign in the center of the pic):

Notice that the racist ideology of white supremacy, an ideology that permeates U.S. history, does not appear on my list except marginally (see #1). That’s because I actually think that, given demographic change (more brown people!) and generational change (“What is all this racist shit about?!?) white supremacy could suddenly flip, in the same way that opposition to gay marriage suddenly flipped. Here’s the problem: even if that happened, all four items on my list would still pertain. Because the success myth, anti-intellectualism, the worship of Freedom!, and the sacred military budget cross all classes, races, genders, and sexual preferences in American society. Those values and beliefs are not going to flip, and sooner or later they are going to bring down the empire.

UPDATE, February 2024

5. The media, both mainstream and social. Mainstream media’s business model demands clicks, viewers, and subscriptions to generate ad revenue. They are therefore addicted to generating controversy however they can, at the cost of spewing nonsense and perpetuating falsehoods. In the current election year, for example, Trump is controversial gold, so he gets lots of uncritical attention. Biden’s accomplishments, on the other hand, are boring and get little attention, whereas controversy about his age and his gaffs gets lots and lots of attention. Social media, meanwhile, is a cesspool of lies, disinformation, and propaganda. The results are poisonous to democracy and exacerbate the habitual distrust of intellectualism and education in the culture (see #2, above). If no one knows the truth, or if there simply is no truth, what’s the point of trying to inform yourself? Just keep scrolling, and share the juicy stuff with your friends.

The modern re-issue of a classic: Rogers Dynasonic Snare Drum. What a beauty!

Link: http://www.rogersdrumsusa.com/model-no-33-dyna-sonic-snare-drum/

L to R: George Mitchell (subbing for Gordon Lee), Stan Bock, Tim Gilson, John Nastos, Derek Sims, Renato Caranto. Invisible, behind the drums, the fabulous Mel Brown. Performing at Christo’s Pizzeria Lounge June 9, 2018.

L to R: George Mitchell (subbing for Gordon Lee), Stan Bock, Tim Gilson, John Nastos, Derek Sims, Renato Caranto. Invisible, behind the drums, the fabulous Mel Brown. Performing at Christo’s Pizzeria Lounge June 9, 2018.

What a joy and an inspiration it has been to hear these master musicians once a month at Christo’s! If you live within an hour’s drive of Salem, Oregon and you miss one of their performances, shame on you.

I wish Hedges could write without hyperventilating, because his inflated rhetoric undercuts his message.

I share his pessimism about the future of America, but I think the reasons for pessimism go deeper than the surface-level events he lists.

I can imagine even white supremacy finally being overturned, just as homophobia has been. But I can’t imagine the success myth, anti-intellectualism, or the religious worship of Freedom disappearing from American culture, and it seems to me that these values, deep-baked into the culture, produce most of the ills that Hedges writes about.

Read Hedges’ article here: https://www.truthdig.com/articles/the-coming-collapse/.

George Eliot on the suspicions of country folk:

In that far-off time superstition clung easily round every person or thing that was at all unwonted, or even intermittent and occasional merely, like the visits of the pedlar or the knife-grinder. No one knew where wandering men had their homes or their origin; and how was a man to be explained unless you at least knew somebody who knew his father and mother? To the peasants of old times, the world outside their own direct experience was a region of vagueness and mystery: to their untravelled thought a state of wandering was a conception as dim as the winter life of the swallows that came back with the spring; and even a settler, if he came from distant parts, hardly ever ceased to be viewed with a remnant of distrust, which would have prevented any surprise if a long course of inoffensive conduct on his part had ended in the commission of a crime; especially if he had any reputation for knowledge, or showed any skill in handicraft. All cleverness, whether in the rapid use of that difficult instrument the tongue, or in some other art unfamiliar to villagers, was in itself suspicious: honest folk, born and bred in a visible manner, were mostly not overwise or clever—at least, not beyond such a matter as knowing the signs of the weather; and the process by which rapidity and dexterity of any kind were acquired was so wholly hidden, that they partook of the nature of conjuring.

—From Silas Marner, Chapter 1

This is a great article about James Baldwin!

For Baldwin, the whole mythic racial nightmare was based upon “economic arrangements of the Western world [which] are obsolete.” People’s identities as Americans are built on fraudulent terms, terms founded upon criminal economic arrangements. Of the latter, Baldwin told Jamal, “Either the West will revise them or the West will perish.” This was especially acute for white folks gripped in “European hangovers” who fantasized that they had more in common with villagers in Scotland or Ireland than they did with black folks who had been their neighbors (and closer than that!) for generations. Economics and race were mutually reinforcing false witnesses.

Link: http://bostonreview.net/race/ed-pavlic/baldwins-lonely-country

With no control by readers (beyond tracking protection which relatively few know how to use, and for which there is no one approach, standard or experience), and no blood valving by the publishers who bare those readers’ necks, who knows what the hell actually happens to the data?

Answer: nobody can, because the whole adtech “ecosystem” is a four-dimensional shell game with hundreds of players…

Link to full post: https://blogs.harvard.edu/doc/2018/03/23/nothing/

I suggest the OPB interview first, and then the Radio Open Source podcast. Fascinating and important insights.

Links:

Mass surveillance is the business model, and we are being sold.

Another great interview by the invaluable Christopher Lydon on his Radio Open Source podcast. The “cult of wellness” is actually the inevitable result of making healthcare a capitalistic enterprise. It’s why the U.S. spends more per capita than any other nation on healthcare, with indifferent results.

Link: http://radioopensource.org/barbara-ehrenreich-on-the-cult-of-wellness/

Link: “Israeli government denounces Natalie Portman for pulling out of prestigious awards ceremony in protest”

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.—from “The Second Coming,” by W. B. Yeats

Bridges. Airplanes. Political systems. Things fall apart.

“The social media giant has swallowed up the free press, become an unstoppable private spying operation and undermined democracy. Is it too late to stop it?”

“We shouldn’t be asking Facebook to fix the problem. We should be fixing Facebook. It’s our collective misfortune that this perhaps silliest-in-history supercorporation – a tossed-off hookup site turned international cat-video vault turned Orwellian surveillance megavillain – has dragged us all to the very cliff edge of modern technological capitalism.”

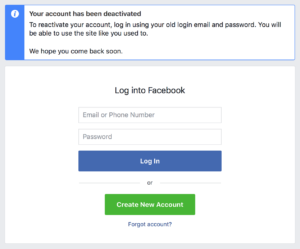

So, deleting Facebook (and Messenger) from your life turns out to be like checking out of Hotel California:

Just in case that print is too small for you: “To reactivate your account, log in using your old login email and password.” In other words, you can delete Facebook, but Facebook will never delete you and your data.

Comical coda: When you go to deactivate (not delete!) your account, you are told that deactivating FB will NOT deactivate Messenger, so after you deactivate FB you need to open Messenger, tap your profile pic, go to Privacy & Terms, and then click “Deactivate.” So, I re-install Messenger, then I deactivate FB on the computer, then I tap my profile pic, Privacy & Terms, “Deactivate”—only to get a message saying that my session has expired. So I log in, repeat the taps, only to find . . . “Deactivate” is not an option anymore! My guess is that logging back into Messenger reactivated my FB account.

At which point I removed my Franz Kafka mask, deleted Messenger from my phone, and walked away.

You cannot lynch me and keep me in ghettos without becoming something monstrous yourselves.

—James Baldwin, 1961

So true. Read the latest news from Gaza and the West Bank to see what the Jews, hapless victims of that monster, Hitler, have become in Israel. Or read Dante and understand that, beyond the endlessly inventive punishments of the damned, the meaning of Hell is quite simple: our punishment is to be who we have become, people who can commit unspeakable crimes and deny them.

The Supreme Court just ruled that a police officer could not be sued for gunning down Amy Hughes. This has vast implications for law enforcement accountability. The details of the case are as damning as the decision. Hughes was not suspected of a crime. She was simply standing still, holding a kitchen knife at her side. The officer gave no warning that he was going to shoot her if she did not comply with his commands. Moments later, the officer shot her four times.

“Shoot first and think later,” according to Justice Sonia Sotomayor, is what the officer did.

From November 9, 2016:

The country that slaughtered Native Americans in the name of God and freedom, that built its wealth on the cruel enslavement of Africans, that elected Andrew Jackson as its president, that stole whatever land it wanted from anyone weak enough to steal it from, that needed a catastrophic civil war to end slavery, that murdered and lynched mercilessly to protect white supremacy, that exploited immigrants, the poor, and the working class to enrich Wall Street and the industrialists, that made racism the law of the land and embedded it in its business practices and system of injustice, that applauded the Dred Scott decision, that promoted ignorance among its people and exploited that ignorance to enrich its ruling elites, that subverted democratic movements around the globe in the name of anti-communism while making billions selling weapons to dictators, that murdered the Kennedys and Martin Luther King, that sent its agents to murder and imprison anyone who seemed to pose a threat while advocating for justice, that obscenely declared making money to be the only value in life—that America has now reasserted itself under the banner of a shameless self-promoting demagogue who promises to make the country great again.

The Americans who produced the Abolitionist movement, who organized the Underground Railroad, who protested against wars of aggression from the Mexican War of 1846 to Vietnam to Iraq, who fought for women’s suffrage and equal rights, who organized labor unions, who marched and demonstrated for civil rights for African-Americans, for immigrants, for homosexuals, for dissidents and those labeled as “other” in a myriad ways, who again and again poured into the streets to endure beatings and abuse and arrest and even death to stand up for justice, who really believe in freedom and justice for all—those Americans will now once again rise to the occasion.

Here is the story of one of those Americans.

Joe Hill (1879 – 1915) immigrated to America from Sweden in his early 20s and worked as a laborer all across the country. He became active in the struggle for labor rights and achieved fame as a writer of songs for the labor movement. In 1914 he was falsely arrested on murder charges, convicted, and finally condemned to death. Before his execution by firing squad he wrote to Bill Haywood, one of the leaders of the IWW (International Workers of the World).

“Don’t waste any time in mourning,” he said to Haywood. “Organize.”

From December 2016:

When my mother died in 1978, after a long illness, it was not a surprise. It was a blessed relief for her, and for her sons. Thus I was totally unprepared for the tsunami of grief that hit me. Slowly I realized that I was not grieving the death of my mother, but the loss of my childhood. I would never “go home” again; I would never be a kid again.

All of us want unconditional love, and for most of us that means mom, and childhood. If you cut through the mishmash of conflicting political impulses behind Donald Trump, “Make America Great Again!” boils down to this: “Let’s re-wind to when I was a kid and I didn’t have all these problems and uncertainties.” Unconvinced? Try asking someone bemoaning the terrible state of the world today, “What era, exactly, would be a better age to live in than this one?” There isn’t one.

Similarly, the howls of outraged grief that follow the death of a pop star from our youth has its roots in the same nostalgia for childhood. Most of us never met these people, and had no personal relationship with them. They function as pieces of furniture decorating our younger, happier days. We are mourning the loss of our youth, not the loss of those people we never knew.

And so as 2016 winds mercifully to a close, we can perhaps find some solace in recognizing that the grieving fans of Prince, George Michael, Carrie Fisher, etc., have more in common than they might imagine with the angry, desperate people who voted for a man who promised to make everything better again.

Memo to Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook CEO:

Dear Mark,

Let’s face it, you are filthy rich several times over. This monetizing-users thing has been a big, big success for you. You don’t need any more money. Your descendants for several generations don’t need any more money. How about you do something for the rest of us?

Make Facebook a free service with zero data collection, zero advertising, zero promoted posts, zero monetizing of users. Pay for ongoing costs with premium services, but keep it free for basic accounts. Make it into a non-profit corporation. Turn it over to some good people to run. Maybe Jimmy Wales of Wikipedia could recommend some to you.

Then go enjoy your money.

“In Women and Power: A manifesto, Mary Beard reveals the ancient roots of misogyny with new and characteristic clarity. Meanwhile, Kate Manne makes the logic of misogyny her subject in Down Girl.”

Link: https://www.the-tls.co.uk/articles/public/women-and-power-down-girl/

King was murdered fifty years ago on April 4th, 1968.

We have deluded ourselves into believing the myth that capitalism grew and prospered out of the Protestant ethic of hard work and sacrifice. The fact is that capitalism was built on the exploitation and suffering of black slaves and continues to thrive on the exploitation of the poor—both black and white, both here and abroad.

—from “The Three Evils of Society,” an address delivered at the National Conference on New Politics, August 31, 1967.

Lest someone object that capitalism arose in Europe where there were no (or very few) black slaves, it should be pointed out that the Industrial Revolution was fueled primarily by textile factories, specifically cotton mills—and that the economic revolution produced by the cotton trade was founded on the labor of enslaved Africans working on the cotton plantations of the American South. For more on this history I strongly recommend Empire of Cotton, by Sven Beckert (2014).

I mean, something happened between 1905 and 1970 besides the Vietnam War. If you want to be a revolutionary and change society, you’ve got to study what happened before. I mean, Lenin and Trotsky studied the French Revolution. The French revolutionaries studied the English revolution. The Founders of the Constitution studied the Greek and Roman revolutions. And they really studied it—it’s in the Constitution, it’s in the Federalist Papers, real knowledge, real absorption and distillation of human political experience.

—from the documentary film, “I. F. Stone’s Weekly” (1973)

His actual presence gave me, in a sense, a shock, and I much regret to have to admit to finding something of the barbaric in his violent stage mannerisms.

The young Jewish element at the back was enthusiastic.

As for Armstrong himself, he was

the ugliest man I have seen on the music-hall stage. He looks, and behaves, like an untrained gorilla.

This savage growling is as far removed from English as we speak or sing it—and as modern—as James Joyce.

—Pops, by Terry Teachout, pp. 186-87

[Moltke, the German Chief of Staff,] did not himself, he said, attach much value to declarations of war. French hostile acts during [recent] days had already made war a fact. He was referring to the alleged reports of French bombings in the Nuremberg area which the German press had been blazing forth in extras all day with such effect that people in Berlin went about looking nervously at the sky. In fact, no bombings had taken place. Now, according to German logic, a declaration of war was found to be necessary because of the imaginary bombings.

—Barbara Tuchman, The Guns of August, p. 110

The turn of events in Belgium was a product of the German theory of terror. Clausewitz had prescribed terror as the proper method to shorten war, his whole theory of war being based on the necessity of making it short, sharp, and decisive. The civil population must not be exempted from war’s effects but must be made to feel its pressure and be forced by the severest measures to compel their leaders to make peace. As the object of war was to disarm the enemy, “we must place him in a situation in which continuing the war is more oppressive to him than surrender.” This seemingly sound proposition fitted into the scientific theory of war which throughout the nineteenth century it had been the best intellectual endeavor of the German General Staff to construct. It had already been put into practice in 1870 when French resistance sprang up after Sedan. The ferocity of German reprisal at that time in the form of executions of prisoners and civilians on charges of franc-tireur warfare startled a world agape with admiration at Prussia’s marvelous six-week victory. Suddenly it became aware of the beast beneath the German skin. Although 1870 proved the corollary of the theory and practice of terror, that it deepens antagonism, stimulates resistance, and ends by lengthening war, the Germans remained wedded to it. As Shaw said, they were a people with a contempt for common sense.

On August 23 placards signed by General von Bülow were posted in Liège announcing that the people of Andenne, a small town on the Meuse near Namur, having attacked his troops in the most “traitorous” manner, “with my permission the General commanding these troops has burned the town to ashes and has had 110 persons shot.” The people of Liège were being informed so that they would know what fate to expect if they behaved in the same manner as their neighbors.

The burning of Andenne and the massacre—which Belgian figures put at 211—took place on August 20 and 21 during the Battle of Charleroi. Hewing to their timetable, harassed by the Belgians’ blowing up of bridges and railroads, Bülow’s commanders dealt out reprisals ruthlessly in the villages they entered. At Seilles, across the river from Andenne, 50 civilians were shot and the houses given over to looting and burning. At Tamines, captured on August 21, sack of the town began that evening after the battle and continued all night and next day. The usual orgy of permitted looting accompanied by drinking released inhibitions and brought the soldiers to the desired state of raw excitement which was intended to add to the fearful effect. On the second day at Tamines some 400 citizens were herded together under guard in front of the church in the main square and a firing squad began systematically shooting into the group. Those not dead when the firing ended were bayoneted. In the cemetery at Tamines there are 384 gravestones inscribed 1914: Fusillé par les Allemands.

When Bülow’s Army took Namur, a city of 32,000, notices were posted announcing that ten hostages were being taken from every street who would be shot if any civilian fired on a German. The taking and killing of hostages was practiced as systematically as the requisitioning of food. The farther the Germans advanced, the more hostages were arrested. At first when von Kluck’s Army entered a town, notices immediately went up warning the populace that the burgomaster, the leading magistrate, and the senator of the district were being held as hostages with the usual warning as to their fate. Soon three persons of prestige were not enough; a man from every street, even ten from every street were not enough. Walter Bloem, a novelist mobilized as a reserve officer in von Kluck’s Army whose account of the advance to Paris is invaluable, tells how in villages where his company was billeted each night, “Major von Kleist gave orders that a man or, if no man was available, a woman, be taken from every household as a hostage.” Through some peculiar failure of the system, the greater the terror, the more terror seemed to be necessary.

When sniping was reported in a town, the hostages were executed. Irwin Cobb, accompanying von Kluck’s Army, watched from a window as two civilians were marched between two rows of German soldiers with fixed bayonets. They were taken behind the railroad station; there was a sound of shots, and two litters were carried out bearing still figures covered by blankets with only the rigid toes of their boots showing. Cobb watched while twice more the performance was repeated.

Visé, scene of the first fighting on the way to Liège on the first day of the invasion, was destroyed not by troops fresh from the heat of battle, but by occupation troops long after the battle had moved on. In response to a report of sniping, a German regiment was sent to Visé from Liège on August 23. That night the sound of shooting could be heard at Eysden just over the border in Holland five miles away. Next day Eysden was overwhelmed by a flood of 4,000 refugees, the entire population of Visé except for those who had been shot, and for 700 men and boys who had been deported for harvest labor to Germany. The deportations, which were to have such moral effect, especially upon the United States, began in August. Afterward when Brand Whitlock, the American Minister, visited what had been Visé he saw only empty blackened houses open to the sky, “a vista of ruins that might have been Pompeii.” Every inhabitant was gone. There was not a living thing, not a roof.

At Dinant on the Meuse on August 23 the Saxons of General von Hausen’s Army were fighting the French in a final engagement of the Battle of Charleroi. Von Hausen personally witnessed the “perfidious” activity of Belgian civilians in hampering reconstruction of bridges, “so contrary to international law.” His troops began rounding up “several hundreds” of hostages, men, women, and children. Fifty were taken from church, the day being Sunday. The General saw them “tightly crowded—standing, sitting, lying—in a group under guard of the Grenadiers, their faces displaying fear, nameless anguish, concentrated rage and desire for revenge provoked by all the calamities they had suffered.” Von Hausen, who was very sensitive, felt an “indomitable hostility” emanating from them. He was the general who had been made so unhappy in the house of the Belgian gentleman who clenched his fists in his pockets and refused to speak to von Hausen at dinner. In the group at Dinant he saw a wounded French soldier with blood streaming from his head who lay dying, mute and apathetic, refusing all medical help. Von Hausen ends his description there, too sensitive to tell the fate of Dinant’s citizens. They were kept in the main square till evening, then lined up, women on one side, men opposite in two rows, one kneeling in front of the other. Two firing squads marched to the center of the square, faced either way, and fired till no more of the targets stood upright. Six hundred and twelve bodies were identified and buried, including Félix Fivet, aged three weeks.

The Saxons were then let loose in a riot of pillage and arson. The medieval citadel, perched like an eagle’s nest on the heights of the right bank above the city it had once protected, looked down upon a repetition of the ravages of the Middle Ages. The Saxons left Dinant scorched, crumbled, hollowed out, charred, and sodden. “Profoundly moved” by this picture of desolation wrought by his troops, General von Hausen departed from the ruins of Dinant secure in the conviction that the responsibility lay with the Belgian government “which approved this perfidious street fighting contrary to international law.”

The Germans were obsessively concerned about violations of international law. They succeeded in overlooking the violation created by their presence in Belgium in favor of the violation committed, as they saw it, by Belgians resisting their presence.

—From The Guns of August, by Barbara Tuchman.

From the “Half-Right, Pretty Good” Dept.

1914: The British Ambassador to the United States, Cecil Spring-Rice,

reported that [President Woodrow] Wilson had said to him ‘in the most solemn way that if the German cause succeeds in the present struggle the United States would have to give up its present ideals and devote all its energies to defense which would mean the end of its present system of government.’

—From Barbara W. Tuchman, The Guns of August.

Barbara Tuchman, in The Proud Tower, describes the political philosophy of Lord Salisbury, the British Prime Minister:

Class war and irreligion were to him the greatest evils and for this reason he detested Socialism, less for its menace to property than for its preaching of class war and its basis in materialism, which meant to him a denial of spiritual values. He did not deny the need of social reforms, but believed they could be achieved through the interplay and mutual pressures of existing parties. The Workmen’s Compensation Act, for one, making employers liable for work-sustained injuries, though denounced by some of his party as interference with private enterprise, was introduced and passed with his support in 1897.

He fought all proposals designed to increase the political power of the masses. When still a younger son, and not expecting to succeed to the title, he had formulated his political philosophy in a series of some thirty articles which were published in the Quarterly Review in the early 1860’s, when he was in his thirties. Against the growing demand at that time for a new Reform law to extend the suffrage, Lord Robert Cecil, as he then was, had declared it to be the business of the Conservative party to preserve the rights and privileges of the propertied class as the “single bulwark” against the weight of numbers. To extend the suffrage would be, as he saw it, to give the working classes not merely a voice in Parliament but a preponderating one that would give to “mere numbers a power they ought not to have.” He deplored the Liberals’ adulation of the working class “as if they were different from other Englishmen” when in fact the only difference was that they had less education and property and “in proportion as the property is small the danger of misusing the franchise is great.” He believed the workings of democracy to be dangerous to liberty, for under democracy “passion is not the exception but the rule” and it was “perfectly impossible” to commend a farsighted passionless policy to “men whose minds are unused to thought and undisciplined to study.” To widen the suffrage among the poor while increasing taxes upon the rich would end, he wrote, in a complete divorce of power from responsibility; “the rich would pay all the taxes and the poor make all the laws.”

He did not believe in political equality. There was the multitude, he said, and there were “natural” leaders. “Always wealth, in some countries birth, in all countries intellectual power and culture mark out the man to whom, in a healthy state of feeling, a community looks to undertake its government.” These men had the leisure for it and the fortune, “so that the struggles for ambition are not defiled by the taint of sordid greed. . . . They are the aristocracy of a country in the original and best sense of the word. . . . The important point is, that the rulers of a country should be taken from among them,” and as a class they should retain that “political preponderance to which they have every right that superior fitness can confer.

There was a nation in the land of America, whose name was USA; and that nation was perfect and upright, and one that feared God, and eschewed evil.

And there were living therein some three hundred million souls.

The nation’s wealth was infinitely more than seven thousand sheep, and three thousand camels, and five hundred yoke of oxen, and five hundred she asses; so that this nation was the greatest of all the nations in the world.

And its citizens went and feasted in their houses, every one his day; and sent and called for their fellow citizens to eat and to drink with them.

And it was so, when the days of their feasting were gone about, that the leaders of the nation sent and sanctified them, and rose up early in the morning, and offered burnt offerings according to the number of them all: for the leaders said, It may be that our citizens have sinned, and cursed God in their hearts.

Now there was a day when the sons of God came to present themselves before the LORD, and Satan came also among them.

And the LORD said unto Satan, Whence comest thou? Then Satan answered the LORD, and said, From going to and fro in the earth, and from walking up and down in it.

And the LORD said unto Satan, Hast thou considered USA, that there is no nation like it in the earth, a perfect and an upright state, one that feareth God, and escheweth evil?

Then Satan answered the LORD, and said, Doth USA fear God for nought?

Hast not thou made an hedge about these Americans, and about their houses, and about all that they have on every side? thou hast blessed the work of their hands, and their substance is increased in the land.

But put forth thine hand now, and touch all that they have, and they will curse thee to thy face.

And the LORD said unto Satan, Behold, all that they have is in thy power; only upon the Pentagon put not forth thine hand. So Satan went forth from the presence of the LORD.

And Satan found a man named Trump, from whose mouth spewed bullshit at every breath; and Satan said, I shall make this man President.

And Satan went to speak with the Russians . . . .

Information has, in the internet age, moved to the forefront in the arsenal of weapons used in political and international struggles. China emphasizes defensive measures in the new information wars, investing heavily in its “Great Firewall” to cut off its citizens’ access to news and ideas the government deems inappropriate or dangerous. Russia is taking the offensive approach, flooding the media with disinformation to such an extent that many people, not knowing what to believe, cease to believe anything they read or hear. The United States, with its Wild West adulation of “Freedom!” above all, has proved particularly vulnerable to the torrent of lies and half-truths found today on the internet. In their responses to this torrent, Americans resemble the young students I have taught over the years. When a claim or idea they previously believed to be true is shown to be false, they rush to the conclusion that there is no truth at all. When political leaders they had formerly admired, or at least had assumed to be honorable, turn out to have been dishonest, they rush to the conclusion that all politicians are corrupt. “The system is rotten to the core!” people exclaim, and others from all points on the political spectrum nod their heads vigorously.

But there are honest, conscientious politicians, and there is a difference between truth and lies. So how can we recover our footing? Our response to these challenges may well determine whether the democratic experiment begun in America in 1776 continues, or whether the chaos grows so pervasive that Americans decide that, for the moment at least, they would prefer more order and less freedom.

Many people wiser and more experienced than I will have ideas, but here are three to start with—none of which is original to me.

•We need to make it possible to run for political office without having to raise millions of dollars. Our politicians should not have to spend their time fundraising instead of working to solve our society’s problems, and they should never have to feel pressured by rich donors and special-interest groups who, if offended, could engineer their defeat in the next election.

•We need to reform or replace PBS and NPR so that we have a completely non-partisan, independently-funded, non-profit source of news that is freely accessible to all. Commercial media organizations depend on advertising for their funding, which means they must keep their ratings as high as possible by publishing sensational content, while avoiding the sort of “boring,” long-form material that would actually do justice to the complex political and social and economic issues before us. Dependence on advertisers also means that commercial media organizations are subject to pressure from their advertisers to avoid controversial material.

•We need to honor education, and educated people. We need to promote education as a good in and of itself, in addition to whatever economic benefits it may bring. The deeply-ingrained suspicion of education in American culture, the denigration of “intellectuals,” the insistence that ignorance and manual labor go together, and that the ignorant manual laborer is more admirable than the ivory-tower university professor—these attitudes are unsustainable in a democracy that depends on every citizen being educated, well-informed, and highly skilled in the critical thinking that, today more than ever, citizens must employ to make wise decisions in the voting booth.

Discuss.

I was sufficiently aware of Mao Zedong’s attempts to export ‘people’s war’ to believe that the United States could not afford to lose in Vietnam. In that, too, I was distinctly a man of my times. It proved to be a disastrously wrong position. The problem was that I knew too much about the international Communist movement and not enough about the United States government and its Department of Defense. I was also in those years irritated by campus antiwar protesters, who seemed to me self-indulgent as well as sanctimonious and who had so clearly not done their homework [on the history of communism in East Asia]… As it turned out, however, they understood far better than I did the impulses of a Robert McNamara, a McGeorge Bundy, or a Walt Rostow. They grasped something essential about the nature of America’s imperial role in the world that I had failed to perceive. In retrospect, I wish I had stood with the antiwar protest movement. For all its naïveté and unruliness, it was right and American policy wrong.

Link: http://www.tomdispatch.com/archive/175286/chalmers_johnson_portrait_of_a_sagging_empire

“This documentary tells the story of a 250-year-old choral tradition from the coast of Labrador. When German Moravian missionaries sailed into Inuit communities with freshly written musical scores by Bach, Handel and others, they couldn’t have forseen the longlasting impact that music would have on the identity of the Inuit of Nunatsiavut. Musicologists now know that many hymns made their North American debut in the wooden churches of Makkovik, Nain, Okak and Hopedale and that some of the music credited to Germans was in fact written by Inuit composers. The first half of the documentary takes place in the small Inuit community of Hopedale where a choir camp has gathered the new generation of singers. The second half takes place in St. John’s where two choirs, an Inuk soprano and 25 symphony players are preparing for a massive concert celebrating this music. Angela Antle is a member of one of the choirs and tells part of this story as a singer, learning the Inuktitut text and discovering that the Inuit left much more than seal oil thumbprints on the corners of the scores, they used the music to help define their identity.”

Link:

http://www.cbc.ca/listen/shows/atlantic-voice/episode/15532542

This is really heartwarming, and heartbreaking.

‘Maria Cioffi was 11 when war broke out in the Balkans, a bloody conflict in which U.N. rules forced Canadian peacekeepers to stand by and watch the slaughter. Now, 25 years later, a letter written by Cioffi is bringing solace to the soldiers who have been haunted by their helplessness.’

Link:

http://www.cbc.ca/listen/shows/the-current/segment/15532086

‘Want to freak yourself out? I’m going to show just how much of your information the likes of Facebook and Google store about you without you even realising it.’

‘One of the primary creators of this unintelligible academic rhetoric, Judith Butler, is best known for her theory of gender performance central to her 1990 book “Gender Trouble.” Yet in recent years, one cannot be sure that even Butler understands her own writing . . . .’

‘How did we arrive at this moment where learning means parroting incoherent political rhetoric?’

Link: https://www.truthdig.com/articles/from-identity-politics-to-academic-masturbation/

Rich Lowry on why Trump and the Republicans are joined at the hip:

Trump’s welfare is inextricably caught up with the party’s. Every point his approval rating ticks up means fewer House seats lost in the midterms. It’s quite possible that in 2020 his prospects will be the difference between Republicans controlling one or more of the elected branches in Washington, or unified Democratic control.

Link: https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2018/03/28/never-trump-rich-lowry-217756

School, including Harvard, had taught him comparatively little; his fellow collegians had taught him less than he had hoped and wished; independent inquiry had taught him relatively much; and, lead where it might, he had decided to follow the path of self-education. This did not mean he would leave the college. No, he would conform to the faculty’s requirements sufficiently to graduate as expected. Neither did it mean that he would try to dispense with teachers; he would need and be glad to have them, in many instances; but he would try to take charge of his own education completely, including the finding of teachers.

—Both Sides of the Ocean: A Biography of Henry Adams, by Edward Chalfant. Pp. 84-85.

Those inclined to the optimistic view that anti-intellectualism in America dwells primarily in remote Appalachian hamlets, or has been produced by television and its digital descendants, will be dismayed to read Henry Adams’ 1857 assessment of his Harvard College classmates’ reading habits:

There are not . . . twenty students in College who ever read, of their own accord, fifty pages of Homer, or Euripides, or Aeschylus, or Demothenes, or Cicero, either translated or untranslated. The number of those who appreciate or even like the classics is absurdly small. It is so too with modern languages, or nearly so. English literature is the bound [i.e., limit], and even in English literature, little except the lightest and most common portion is at all known. The fishes all swim on the surface, and neither dare nor wish to go deeper.

—from “Reading in College,” published in Harvard Magazine, October 1857, and quoted by Edward Chalfant in the first volume of his biography of Adams.

Chalfant goes on to describe the response to Adams’ critique: “His classmates looked carefully at his ‘Reading in College’ and told him he was conceited” (Both Side of the Ocean: A Biography of Henry Adams, by Edward Chalfant, pp. 83-84).

So there you have it: even at Harvard College in 1857, people who enjoyed reading were regarded as snobs.