America in 2020-21, it turns out, is a lot like America in 1876-77.

The disputed presidential election of 1876 finally resulted in a back-room deal that put the Republican candidate, Rutherford B. Hayes, in the White House. In return, federal troops were removed from the states of the Confederacy, thus ending Reconstruction and marking the start of the Jim Crow era in which Southern whites reasserted political domination of their states through a campaign of terror, intimidation, and racist legislation.

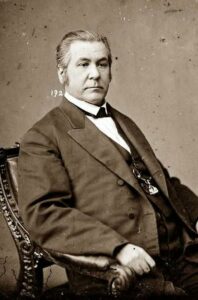

In the following newspaper dispatch from January 1877, Senator John Sherman of Ohio, brother of the Civil War general, William Tecumseh Sherman, debates with . . . my great-great-uncle, Senator Lewis Vital Bogy (1813 – 1877). Bogy—whose own election three years previously was widely reported to have resulted from bribery of the electors—was a Missouri Democrat whose grandfather, Joseph Baugis, was a French-Canadian who had left Quebec at the age of 14 and arrived in the Mississippi River Valley, where he engaged in the fur trade and eventually became the owner of eleven slaves on his property in Arkansas. Senator Bogy would die just months after this debate, in September 1877. His brother, Benjamin Ignace Bogy, was my great-great-grandfather. Most of the family (whose name is pronounced with a soft g or zh sound) subsequently became staunch bourgeois Republicans.

The capper to Sen. Bogy’s argument comes when he claims that Southerners “had been forced to resort to violence” and that “Southern whites had a right to rebel against State Governments forced on them by the Federal Government and sustained by Federal bayonets.” Oh, boy. I cannot say I am sorry to have missed those family gatherings with Uncle Lewis.

[It should be noted that Sen. Bogy’s older brother, Joseph Bogy III (1808 – 1881) ran for Congress (unsuccessfully) in 1863 as an “Unconditional Unionist” and did not share the Senator’s political views, at least. On the other hand, his younger brother and, alas, my great-great-grandfather, Benjamin Ignace Bogy (1829 – 1900) joined the Confederate calvary under General Marmaduke.]

CONGRESS.

Washington, January 9th.—SENATE.—By unanimous consent, the House bill absolutely abolishing the District of Columbia Police Commissioners, and to transfer their duties to the District Commissioners, passed.

The resolution ordering the arrest of the recusant witness Runyon passed without division.

Wallace’s resolution concerning the Electoral count was then considered. [Sen. John] Sherman [R-Ohio] spoke at length, and claimed that the evidence before the Louisiana Returning Board justified their action.

The Senate discussed the resolutions of Wallace, in regard to the count of the Electoral vote, during the whole afternoon, when they were laid aside, and the bill to perfect the revision of the Statutes of the United States was taken up, so as to come up as unfinished business to-morrow.

Sherman said the Louisiana Electors had already voted for Hayes and Wheeler. The vote was duly authenticated and delivered to the President of the Senate, and was entitled to credit. Hayes and Wheeler were legally entitled to that vote. He reiterated that Hayes had not sought the office, and would gain no honor by receiving it wrongfully, but if Constitutionally preferred, he was not to be tricked. He (Sherman) would accept any plan for an honest count of the vote. He read from the Louisiana law requiring the Returning Board to reject the votes in parishes where fraud and violence prevailed. He paid a tribute to the honesty of the Board and their respect for the law, rather than the Influence which was brought to bear on them. He reviewed the character of the evidence before the Board, which, he said, compelled them to act as they did about throwing out returns. This violence, he asserted, was to compel men to vote the Democratic ticket and elect Tilden. The intimidation extended to Mississippi, and these votes were to be counted for S. J. Tilden. The evidence before the ; Senate I Committee would show that Henry Pinkston owed his death to cheers uttered at a Republican meeting. If such intimidation extended to other States North and West, law would end. Tilden’s inauguration would be the greatest misfortune that could befall the country. He did not fear Tilden and his four years’ of power, but did fear such means of electing him. Tllden’s term of office would be dishonored from the beginning. The blood of hundreds of men would be on his garments. In Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia improper means had prevented Republicans from voting. In closing, he denied that the Government paid the expenses of the Republican Visiting Committee to New Orleans. Gov. Hayes did not know he was going, nor did Hayes make a suggestion concerning his course there. He was proud of the willingness of the country to acquiesce in the result.

[Sen. Lewis V.] Bogy [D-Missouri] said he had heard the most humiliating effort ever made upon the floor of the Senate. Sherman’s speech amazed him. It was incomprehensible. If Sherman spoke truly of the condition of things in Louisiana, then the country had retrograded to the darkest ages of barbarism. If Louisians were assassins, it, disgraced the country as well as that State. He denounced the testimony alluded to by Sherman as that of villains and perjurers. He would, in the future, explain how the crimes in Louisiana were brought about, on account of the recent emancipation of a race not yet in a condition to enjoy the privileges given them by the Constitution. Kellogg, Packard and other men were responsible for the condition of things in that State. Whites there were as peaceable and law-abiding as anywhere. Tilden should not be inaugurated, if elected as Sherman claimed; but he was honestly elected.

Boutwell and Bogy engaged in a discussion of some length, involving the question of outrages in Mississippi, Bogy claiming that the Mississippi Committee last year had greatly exaggerated the facts, and had the worst witnesses before them.

Boutwell denied this. He wondered that a people who had spent so much money and lost so many lives for the perpetuity of the Union would calmly see such outrages in the South.

Bogy retorted by alluding to the carpet-baggers sent South by Boutwell and his friends to administer Governments. He particularly denounced the Ames Administration as an outrage and disgrace to the country. The negroes in Mississippi were now treated with more respect than in Massachusetts. Southern whites had been forced to resort to violence, as the people of San Francisco had some years ago. It was the great American common law of self-defence.

Boutwell and Sherman said that was admitting that violence prevailed there. Sherman said the people of New York, when Tweed stole his millions, did not resort to violence.

Bogy said the Southern whites had a right to rebel against State Governments forced on them by the Federal Government and sustained by Federal bayonets. . . .

—Daily Alta California, Volume 29, Number 9774, 10 January 1877

https://cdnc.ucr.edu/?a=d&d=DAC18770110.2.33&srpos=129&e=——-en–20–121–txt-txIN-Bogy——-1

Senator Bogy’s character is further illuminated by this 1881 piece recalling his interaction with a fellow Senator, Blanche Kelso Bruce.

Senator Bruce (1841 – 1898) was the first African-American elected to the Senate to serve a full term. He was defeated for re-election in 1880 by a white Democrat and former Confederate officer in the Civil War. Bruce was just one of many black politicians who lost their offices after Reconstruction ended in 1877. The son of a white plantation owner and one of his house-slaves, Bruce studied at Oberlin College for two years. When the Civil War began he deliberately went to Kansas, a “free state,” to gain his freedom (and almost lost his life in Quantrill’s raid on Lawrence, Kansas in 1863—see the link to his 1886 newspaper interview, below). In 1864 he opened a school for black children in Mark Twain’s hometown, Hannibal, Missouri. —Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blanche_Bruce.

A Story of Two Senators

The late Senator Bogy of Missouri was anxious to have a pension-bill passed one day for a constituent, and came over to the Republican side to ask support for it. He approached the colored Senator from Mississippi [Sen. Blanche Bruce, elected in 1874, the same year that Bogy was elected], and said:

“Now look here, Bruce, vote for this, won’t you? I only want another vote or two, and you can carry it through for me. It is a meritorious case.”

“Certainly,” said Senator Bruce. “You know, Senator, that I have always been willing to do you any favor you asked.”

“Sir,” replied the Missouri Senator, “I never asked you a favor in my life till this moment.”

“Oh, yes, you have,” replied Bruce. “You may remember once, many years ago, that you were going from St. Louis down the river on a steamboat, and you were hurrying along to catch the boat with a big valise. You passed a little barefooted mulato, and said: ‘Here, you little black rascal, take this valise and come on with me.’ The boy took the hand-bag, and when you came near the boat, you saw it was about to push off, and you ran on ahead and just crossed the gang-plank when it was drawn in. The boy, however, had not been able to keep up with you, and arrived too late. You stood on the lower deck and yelled: ‘Throw that valise aboard, you black rascal; I can’t go without my valise.’ But the boat moved out till the boy was afraid it would fall into the river if be tried to throw it, and, besides, he expected to receive a quarter for carrying it, and you had, apparently, forgotten all about that. The valise was not thrown and you made the captain of the boat come back to the dock again to get it, and the boy collected the quarter. Now do you remember that circumstance, Senator?” concluded Bruce.

“I do,” admitted Senator Bogy.

“Well,” said Bruce, “I was the little mulatto-boy that carried your valise, and I am just as ready to accommodate you to-day as I was then. I’ll vote for your bill.”

—The Weekly Calistogian, Volume IV, Number 16, 6 April 1881

https://cdnc.ucr.edu/?a=d&d=TWC18810406.2.6&srpos=241&e=——-en–20–241–txt-txIN-Bogy——-1

Twelve years after that story was published, Frank G. Carpenter re-told it rather differently in the San Francisco Call:

Returning to Senator Bruce: He had a number of curious experiences during that first term in the Senate, and one of the queerest of these was when old Senator Bogy asked him to vote for a bill which he had before the Senate. Bogy was one of the most aristocratic of the Senators. He came from an old St. Louis family, and as he asked Bruce to do this, he sat down beside him. Bruce laughed as he made the request, and said, “Senator Bogy, I think we can arrange this transaction better than we did our last business matter.”

“What do you mean?” said Bogy. “I never did any business with you before.”

“Don’t you remember meeting me before coming to the Senate?” said Bruce.

“No, I do not,” replied Bogy.

“Well,” said Bruce, “I am not surprised at that, for it was more than twenty years ago. You were trying to catch a steamer at St. Louis and you had a heavy bag with you. The day was hot and the perspiration was rolling off you in streams. A colored boy ran up to you and grabbed the bag, and he carried it for you to the wharf. You got there just as the boat was about to start. You jumped on and called for the valise. The colored boy stuck to the valise and called for his quarter. You had to go through every one of your pockets before you could find a quarter and throw it ashore. Then the boat was too far out for the boy to throw the valise. The captain had to stop the boat and come back to the wharf for you to get your valise. Now, do you remember?”

“Yes, I remember,” replied Senator Bogy; “but I don’t see where you come in.”

“Oh,” replied Bruce, “I was the colored boy who got the quarter.”

—San Francisco Call, Volume 74, Number 151, 29 October 1893

https://cdnc.ucr.edu/?a=d&d=SFC18931029.2.132&srpos=462&e=——-en–20–461–txt-txIN-Bogy——-1

In an 1886 newspaper interview, Bruce told the story himself, again in a slightly different way:

A SINGULAR INCIDENT, worth relating, occurred when I was a member of the Senate. I had never exchanged a word with Mr. Bogy, then a Senator from Missouri. We knew each other merely by sight. One day, to my surprise, Senator Bogy came to my desk and explained that he was much interested in the passage of a certain bill. There was nothing in it of a political nature, and he invoked my active assistance to help him pass the measure. He did not then realize that we had ever met before, but I well remembered the circumstance. I listened to his statement, and then replied about as follows :

“It will afford me pleasure, Senator, to oblige you in any way, but really, you used me so shamefully in the last business transaction we had together, I am suspicious of you.”

“Why, sir, what do you mean?” excitedly replied the Missouri Senator, “we have never met before that I can recollect, and certainly have never had any business transactions together of any character.”

“Let me see,” I replied, “whether I cannot recall a certain transaction to your memory. Some twenty years ago a gentleman was hurrying through the streets of St. Louis one day, endeavoring to catch and board a river steamer. He was embarrassed with a heavy valise, and noticing a colored boy near by, asked if he did not want to earn a quarter. The boy replied affirmatively, and the valise was handed him to carry. The gentleman and the colored boy ran to the river together, and the gentleman jumped on board the boat just as the gang-plank was being drawn in. He halloed to the boy to throw the valise on board, but the boy halloed back to first give him the promised quarter. This the gentleman refused to do, and the result was the boat, which had drifted far out into the stream, was put again to shore. The gentleman, thereupon, somewhat unwillingly, handed out the quarter, and the boy gave up the valise, not, however, without escaping a round denunciation and fist-shaking from the angry gentleman, in which the words ‘black rascal’ were freely uttered in terms more forcible than polite.”

“Yes,” replied Senator Bogy, “I remember the incident as well as if it had occurred yesterday. I was the gentleman, and we had quite a scene of it. But what has that do with any business transaction between us?”

“Very much!” I replied laughingly, “since you were the gentleman and I was the colored boy whom you endeavored, while in haste to catch the boat, to beat out of a quarter of a dollar he had fairly, earned.” Senator Bogy laughed heartily at the reminiscence, and we shook hands. I helped him pass his bill just to demonstrate that strange things frequently happen in this world, and that I bore him no malice. Who could have foreseen that the irate gentleman and the colored slave boy would have met years afterward as peers and colleagues in the Senate of the United States!

—Daily Alta California, Volume 41, Number 13563, 18 October 1886

https://cdnc.ucr.edu/?a=d&d=DAC18861018.2.21&srpos=1194&e=——-en–20–1181–txt-txIN-Bogy——-1

For the full interview with Senator Bruce, see “Senator Blanche K. Bruce’s story, in his own words.”

Having characters like Senator Bogy in my family tree, and growing up where I did, made me wonder how I ever turned out so differently. For my answer, have a look at Dear Maury.

Wonderful bit of history! Also, perhaps the word recusant will make a comeback.

That’s great stuff, Eric, thanks!

Cracks me up to know of such characters from our ancestral past. All their actions and staunch beliefs. Thank goodness we can evolve.

I have often wondered how our 1907-born, Birmingham, Alabama father would have reacted to my first girlfriend with her big 1973 afro.

Yeah, I doubt that would have gone very well.

I am more inclined to be recumbent than recusant these days . . .

The plot ever thickens in your family, E.

No kidding! What a crowd . . . .

I am also descendent of the Bogys. Would like to connect to learn more on the history. It’s quite peculiar from my research.